ウィリアム・キングドン・クリフォード

この項目「ウィリアム・キングドン・クリフォード」は翻訳されたばかりのものです。不自然あるいは曖昧な表現などが含まれる可能性があり、このままでは読みづらいかもしれません。(原文:en:William Kingdon Clifford oldid=1245928067) 修正、加筆に協力し、現在の表現をより自然な表現にして下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴も参照してください。(2024年12月) |

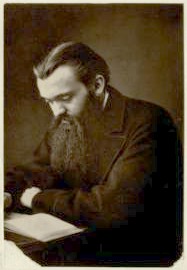

| ウィリアム・クリフォード William Clifford | |

|---|---|

William Kingdon Clifford (1845–1879) | |

| 生誕 |

1845年5月4日 イングランド、デヴォン、エクセター |

| 死没 |

1879年3月3日 ポルトガル、マデイラ |

| 研究分野 |

数学 哲学 |

| 研究機関 | ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドン |

| 出身校 |

キングス・カレッジ・ロンドン ケンブリッジ大学、トリニティ・カレッジ |

| 博士課程 指導学生 | アーサー・ブラック |

| 主な業績 |

クリフォード代数 クリフォードの定理 クリフォードの定理 クリフォードトーラス クリフォード–クライン形式 クリフォード平行 ベッセル–クリフォード関数 双対四元数 Elements of Dynamic |

| プロジェクト:人物伝 | |

ウィリアム・キングドン・クリフォード(英: William Kingdon Clifford、1845年5月4日 – 1879年3月3日 、FRS)は、イギリスの数学者、哲学者。ヘルマン・グラスマンの作品を基に、現在幾何代数と呼ばれる概念を導入した。この特殊な場合は彼を敬してクリフォード代数と命名されている。幾何代数の演算は、新たな位置にモデル化された幾何学的対象を鏡映、回転、平行移動、射影する効果がある。一般のクリフォード代数と特有の幾何代数は数理物理学[1]、幾何学[2]、コンピューティング[3]のような分野において、重要性を増してきた。クリフォードは、重力が根底の幾何学の表れであるだろうということを最初に提言した。哲学の著作では、クリフォードは mind-stuff という表現を作り出した。

経歴

[編集]エクセターに生まれ、ベッドフォードサーカスのテンプルトン博士の学校で教育を受け、有望な将来性を呈した[4]。15歳からキングス・カレッジ・ロンドン、そしてトリニティ・カレッジに通った。1867年、セカンドラングラーと年内2人目のスミス賞受賞者として卒業し、1868年フェローに選出された[5][6]。1870年、1870年12月22日の日食を観測するためのイタリアへの遠征隊に組み込まれた。旅の間、シチリア沖で難破に見舞われたが生き残った[7]。

1871年、ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンの数学・力学の教授に指名され、1874年に王立協会フェローに選ばれた[5]。ロンドン数学会と形而上学会にも属していた。

1875年4月7日、ルーシー・レーンと結婚し、2人の子を設けた[8]。クリフォードは子供との戯れを楽しみ、童話コレクション The Little People を制作している[9]。

死没

[編集]1876年、クリフォードはおそらく過労によって引き起こされたであろう衰弱に悩まされた。彼は昼間は生徒の指導、夜間は執筆活動をする生活を送っていた。アルジェリアとスペインでの半年の休暇を通じて、クリフォードは18か月間仕事に戻ることができたが、その後もう一度体調を崩した。妻子を残してマデイラの島で療養を試みたが、数か月後に結核で没した。

クリフォードとその妻ルーシーはロンドンのハイゲイト墓地の、ジョージ・エリオットとハーバート・スペンサーの墓近辺、カール・マルクスの墓の北側に埋葬された。

学術雑誌 Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras はクリフォードの運動学と抽象代数学の遺稿を出版している。

数学

[編集]

"Clifford was above all and before all a geometer."

非ユークリッド幾何学の発見は、クリフォードの時代の幾何学に新たな可能性を拓いた。本質的な微分幾何学が生まれ、曲率の概念が曲線・曲面だけでなく空間にも適用されるようになった。クリフォードはベルンハルト・リーマンの1854年のエッセイ "On the hypotheses which lie at the bases of geometry"に強く心を打たれた[10]。1870年、クリフォードはケンブリッジ哲学会にリーマンの湾曲空間の概念を、重力による空間の湾曲に関する推測を含めて報告した。リーマンの論文のクリフォードによる翻訳版は1873年にネイチャーで掲載された[11][12]。1876年に発表されたケンブリッジ大学での報告書"On the Space-Theory of Matter"ではアインシュタインの一般相対性理論をその40年前に予期していた。クリフォードは非ユークリッド距離空間として楕円空間幾何学の研究に打ち込んだ。楕円空間上の等距離曲線は現在クリフォード平行線と呼ばれる。

クリフォードと同時期の人々は、彼を鋭敏で独創的、ウィットに富み温厚な人物だと評した。クリフォードは論文で斉次多項式から射影幾何学まで幅広い主題を扱い、力学の教科書 Elements of Dynamic も出版した。グラフ理論の不変式論への応用は、ウィリアム・スポッティスウードとアルフレッド・ケンペに先んじていた[13]。

代数学

[編集]1878年、クリフォードは、グラスマンによって拡張された代数をもとに独創的な作品を発表した[14]。この論文で、ウィリアム・ハミルトンの開発した四元数と、グラスマンの直積(外積)を統一することに成功した。彼はグラスマンの創造の幾何学的自然さ、そしてグラスマンが発展させた代数学に四元数がうまく整合することを理解していた。四元数におけるベンソルは、回転の表現を簡潔にする。クリフォードは、内積とグラスマンの外積の和からなる幾何学的な積の基礎を築いた。後にこの概念はリース・マルツェルによって形式化された。 内積は、直線や平面や体積や角や距離を組み込むに十分な、計量を幾何代数に備えつける。一方外積は平面や体積に有向性のようなベクトル的な性質を加える。

この2つの積を組み合わせることで、除算演算が可能になる。これは、空間内の対象がいかにして相互に影響するかということの質的な理解を大幅に広げた。さらに、これらの相互的影響の空間的な結果を量的に計算する手段を提供した。クリフォードが呼んだように、幾何代数の結果は、最終的に3次元空間の対称の運動と射影を反映する代数の構築の長い目標[i]を達成した[15]。

更に、クリフォードの代数的構造は高次元に拡張される。代数的演算は2,3次元と同様に、同じ形式となっている。一般のクリフォード代数の重要性は時間とともに増し、同型写像のクラスは実代数と同様に、四元数でない他の数学体系においても定義されている[16]。

実解析と複素解析の領域は、4次元に埋め込まれた三次元球面の概念のおかげで、四元数Hの代数学を通じて拡大した。3次元球面の中にある四元数ベンソルは回転群 SO(3)の表現をもたらす。クリフォードはハミルトンの双四元数は有名な代数のテンソル積であると述べ、 代わりにHの他の2つのテンソル積を提案した。すなわち、クリフォードは複素数Cから取られた"スカラー"は、代わりに分解型複素数Dまたは二重数Nから取られるかもしれないと主張した。テンソル積を用いれば、は分解型双四元数を作り、は双対四元数を成すといえる。双対四元数の代数は運動学の通常のマッピングスクリュー配置に使われる。

哲学

[編集]哲学者として、クリフォードの名は主に2つの語mind-stuff 、tribal self から連想される。前者はクリフォードの形而上学的概念を象徴しており、彼がスピノザの著書を読んでいたことが窺える[5]。 クリフォードは mind-stuff を次のように定義した[18]。

That element of which, as we have seen, even the simplest feeling is a complex, I shall call Mind-stuff. A moving molecule of inorganic matter does not possess mind or consciousness; but it possesses a small piece of mind-stuff. When molecules are so combined together as to form the film on the under side of a jelly-fish, the elements of mind-stuff which go along with them are so combined as to form the faint beginnings of Sentience. When the molecules are so combined as to form the brain and nervous system of a vertebrate, the corresponding elements of mind-stuff are so combined as to form some kind of consciousness; that is to say, changes in the complex which take place at the same time get so linked together that the repetition of one implies the repetition of the other. When matter takes the complex form of a living human brain, the corresponding mind-stuff takes the form of a human consciousness, having intelligence and volition.—"On the Nature of Things-in-Themselves" (1878)

クリフォードの概念について、フレデリック・ポロックは次のように述べている。

Briefly put, the conception is that mind is the one ultimate reality; not mind as we know it in the complex forms of conscious feeling and thought, but the simpler elements out of which thought and feeling are built up. The hypothetical ultimate element of mind, or atom of mind-stuff, precisely corresponds to the hypothetical atom of matter, being the ultimate fact of which the material atom is the phenomenon. Matter and the sensible universe are the relations between particular organisms, that is, mind organized into consciousness, and the rest of the world. This leads to results which would in a loose and popular sense be called materialist. But the theory must, as a metaphysical theory, be reckoned on the idealist side. To speak technically, it is an idealist monism.[5]

一方 Tribal self はクリフォードの論理的観点の鍵を与える。彼の視点は、"tribe"の福祉に貢献する行為を規定する各人それぞれの"self"の発達によって、良心的、道徳的法を説明するものである。クリフォードの当時の名声の多くは彼の宗教に対する姿勢にあった。真実への強い愛と社会的責任への献身に動かされ、彼は、蒙昧主義を好み人間社会の主張より宗教の主張を優先するような教会制度を強く非難した。この警戒は神学がダーウィニズムと不合であったために肥大化し、クリフォードは当時の科学に属する反精神的傾向の危険人物であるとみなされた[5]。Concomitanceと"心身並行説"のクリフォードの教義が、どれほどジョン・ヒューリングス・ジャクソンの神経系モデルや、ジャクソンを通したジャネット、フロイト、ライオット、アイの研究に影響したかについても議論されている[19]。

倫理

[編集]

1877年のクリフォードのエッセイ The Ethics of Belief において彼は証拠が損失したものを信じることは不道徳であると主張した[20]。彼は、ある古くてあまりよい造りではない船に乗客を満載にして海に送る計画を立てた船のオーナーについて述べた。この船のオーナーは船が航海に適していないのではないかという疑問をもっており、この疑問は彼を悩ませ不幸にした( "These doubts preyed upon his mind, and made him unhappy." )。船を改装するには多額の費用がかかると考える。すると、やっとオーナーはこれらのメランコリーの反復を克服することに成功した( "he succeeded in overcoming these melancholy reflections.")。オーナーは軽い心とともに出向する船を見守って...船が海の真ん中で沈み、何も言わなくなったとき、彼は保険金を獲得した("with a light heart…and he got his insurance money when she went down in mid-ocean and told no tales.")[20]。

クリフォードは、オーナーは船に問題がないと心から信じていても、乗客の死に罪悪感を感じると主張した( "[H]e had no right to believe on such evidence as was before him."[ii] )。加えて、彼は船が無事に目的地に到着した場合でも、選択の道徳性は一度決められた時点で永遠に変わらず、盲目的な偶発の実際の結果は重要でないから、結論は依然として不道徳であると説いた。オーナーも少なからず罪があるが、彼の誤った行為は決して見つからない。しかし、当時彼が入手できた情報を考慮すれば、彼に決定権はなかった。

クリフォードはクリフォードの原理として知られるように、次のように結論付けた。 "it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence."[20]

そのため、クリフォードは"blind faith"(証拠が不完全であるのにも関わらず盲目的に信じる事)を美徳とする宗教的思想家に対して、直接的な対抗の意を示している。この論文はプラグマティズムの哲学者ウィリアム・ジェームズに"The Will to Believe"の講演において批判されている。 この2作品は過度な証拠主義、信仰、過信の討論の試金石として一緒に読まれたり出版されたりすることもある。

相対性の予期

[編集]クリフォードは時空と相対性の完璧な理論を構築する事ができなかったものの、彼が印刷物に残した結果には現代的な概念を予期するものも多い。Elements of Dynamic(1878)では、彼は "quasi-harmonic motion in a hyperbola"を導入した。彼の書いた媒介変数表示化された単位双曲線は後世の著者が相対論的変数として利用した。彼は別の印刷物で次のように述べている[21]。

- The geometry of rotors and motors…forms the basis of the whole modern theory of the relative rest (Static) and the relative motion (Kinematic and Kinetic) of invariable systems.[iii]

この文章は双四元数について述べているが、クリフォードはこれを独立した発展形として分解型双四元数にしている。この本は一般相対性理論の本質を突いた"On the bending of space"という章に続く。また、1876年の On the Space-Theory of Matter では、クリフォード自身の見解について議論している。

1910年ウィリアム・バレット・フランクランド(William Barrett Frankland)は Space-Theory of Matter を平行に関する著作の中で引用した("The boldness of this speculation is surely unexcelled in the history of thought. Up to the present, however, it presents the appearance of an Icarian flight."[22])。後年、一般相対性理論がアルベルト・アインシュタインによって進歩すると、多くの学者が、クリフォードはアインシュタインを先取りしていたということを指摘した。例えばヘルマン・ヴァイル (1923)はベルンハルト・リーマンのように、クリフォードは相対性の幾何学的思考を先取りした人物の一人であると言及している[23]。

1940年、エリック・テンプル・ベルは The Development of Mathematics を発表し、この中で、クリフォードの相対性について論じている[24]。

- Bolder even than Riemann, Clifford confessed his belief (1870) that matter is only a manifestation of curvature in a space-time manifold. This embryonic divination has been acclaimed as an anticipation of Einstein's (1915–16) relativistic theory of the gravitational field. The actual theory, however, bears but slight resemblance to Clifford's rather detailed creed. As a rule, those mathematical prophets who never descend to particulars make the top scores. Almost anyone can hit the side of a barn at forty yards with a charge of buckshot.

ジョン・ホイーラーは1960年のスタンフォード大学の国際倫理・方法論・科学哲学会議(CLMPS)で、発起人をクリフォードに帰する一般相対性の幾何動力学の式を紹介した[25]。

The Natural Philosophy of Time (1961) では、ジェラルド・ジェームズ・ホイットローがクリフォードの予見を回想し、フリードマン・ルメートル・ロバートソン・ウォーカー計量について述べるためにクリフォードの語を引用した[26]。

コルネリウス・ランチョス (1970) はクリフォードの予知を次のように要約している[27]。

- [He] with great ingenuity foresaw in a qualitative fashion that physical matter might be conceived as a curved ripple on a generally flat plane. Many of his ingenious hunches were later realized in Einstein's gravitational theory. Such speculations were automatically premature and could not lead to anything constructive without an intermediate link which demanded the extension of 3-dimensional geometry to the inclusion of time. The theory of curved spaces had to be preceded by the realization that space and time form a single four-dimensional entity.

同様にバーネッシュ・ホフマン (1973) は次のように言及している[28]。

- Riemann, and more specifically Clifford, conjectured that forces and matter might be local irregularities in the curvature of space, and in this they were strikingly prophetic, though for their pains they were dismissed at the time as visionaries.

1990年、ルース・ファーウェルとクリストファー・ニー(Christopher Knee)は、クリフォードの先見の承認の記録について調べた[29]。彼らは一般相対性の概念的考えのいくつかを先知したのは、リーマンではなくクリフォードだ("it was Clifford, not Riemann, who anticipated some of the conceptual ideas of General Relativity." )と結論付けた。クリフォードの遠謀の認識の欠損を説明するために、彼らはクリフォードが計量幾何学の専門家であったことに注目し、計量幾何学は追求されるには一般的な認識論ではあまりに難解だ("metric geometry was too challenging to orthodox epistemology to be pursued.)とした[29]。1992年、2人はクリフォードとリーマンの研究を続けた[30]。

[They] hold that once tensors had been used in the theory of general relativity, the framework existed in which a geometrical perspective in physics could be developed and allowed the challenging geometrical conceptions of Riemann and Clifford to be rediscovered.

主な著作

[編集]- 1872. On the aims and instruments of scientific thought, 524–41.

- 1876 [1870]. On the Space-Theory of Matter.[31][32]

- 1877. "The Ethics of Belief." The Contemporary Review 29:289.[20][33]

- 1878. Elements of Dynamic: An Introduction to the Study of Motion And Rest In Solid And Fluid Bodies.[34]

- Book I: "Translations"

- Book II: "Rotations"

- Book III: "Strains"

- 1878. "Applications of Grassmann's Extensive Algebra." American Journal of Mathematics 1(4):353.[35]

- 1879: Seeing and Thinking[36]—次の4つのの人気な科学講演も含む:[5]

- "The Eye and the Brain"

- "The Eye and Seeing"

- "The Brain and Thinking"

- "Of Boundaries in General"

- 1879. Lectures and Essays I & II、フレデリック・ポーロックによる導入付[37]。

- 1881. "Mathematical fragments" (facsimiles).[38]

- 1882. Mathematical Papers, ロバート・タッカー編集。ヘンリー・ジョン・ステファン・スミスの導入付[39]。

- 1885. The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences、カール・ピアソンにより補完[5][40]。

- 1887. Elements of Dynamic 2.[41]

-

"The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences"の1885年のコピー本

-

"The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences"の1885年のコピー本の表紙。

-

"The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences"の1885年のコピー本の目次。

-

"The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences"の1885年のコピー本の最初のページ。

邦訳書籍

[編集]- 菊池大麓 訳『数理釈義』博聞社、1888年。NDLJP:826536。 - 岡潔は、数理釈義を耽読した。特にこの書籍の149,150頁に書かれたクリフォードの定理を神秘的であると形容し、数学の下地を付けてくれたと語っている[42]。

引用

[編集]

"I…hold that in the physical world nothing else takes place but this variation [of the curvature of space]."

— Mathematical Papers (1882)

"There is no scientific discoverer, no poet, no painter, no musician, who will not tell you that he found ready made his discovery or poem or picture—that it came to him from outside, and that he did not consciously create it from within."—"Some of the conditions of mental development" (1882), 王立研究所の講義

"It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence."—The Ethics of Belief (1879) [1877]

"If a man, holding a belief which he was taught in childhood or persuaded of afterwards, keeps down and pushes away any doubts which arise about it in his mind, purposely avoids the reading of books and the company of men that call in question or discuss it, and regards as impious those questions which cannot easily be asked without disturbing it—the life of that man is one long sin against mankind."—The Ethics of Belief (1879) [1877]

"I was not, and was conceived. I loved and did a little work. I am not and grieve not."—Epitaph

関連項目

[編集]- ベッセル–クリフォード関数

- クリフォードの原理

- クリフォード解析

- クリフォード・ゲート

- クリフォード束

- クリフォード加群

- マルチベクトル

- 分解型複素数

- ローター

- 単体

- 分解型双四元数

- The Will to Believe

脚注

[編集]注釈

[編集]- ^ "I believe that, so far as geometry is concerned, we need still another analysis which is distinctly geometrical or linear and which will express situation directly as algebra expresses magnitude directly." Leibniz, Gottfried. 1976 [1679]. "Letter to Christian Huygens (8 September 1679)." In Philosophical Papers and Letters (2nd ed.). Springer.

- ^ 原文

- ^ この文章は"The bending of space."というセクションのすぐ後に書かれている。しかし序文(p.vii)によれば、このセクションはカール・ピアソンによって書かれた。

出典

[編集]- ^ Doran, Chris; Lasenby, Anthony (2007). Geometric Algebra for Physicists. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 592. ISBN 9780521715959

- ^ Hestenes, David (2011). “Grassmann's legacy”. From Past to Future: Graßmann's Work in Context. Basel, Germany: Springer. pp. 243–260. doi:10.1007/978-3-0346-0405-5_22. ISBN 978-3-0346-0404-8

- ^ Dorst, Leo (2009). Geometric Algebra for Computer Scientists. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann. pp. 664. ISBN 9780123749420

- ^ Harvey, Hazel (1996). Exeter Past. Phillimore. pp. 64–66. ISBN 1 86077 006 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chisholm 1911, p. 506.

- ^ "Clifford, William Kingdon (CLFT863WK)". A Cambridge Alumni Database (英語). University of Cambridge.

- ^ Chisholm, M. (2002). Such Silver Currents. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7188-3017-5

- ^ Stephen, Leslie; Pollock, Frederick (1901). Lectures and Essays by the Late William Kingdon Clifford, F.R.S. 1. New York: Macmillan and Company. p. 20. オリジナルの3 March 2008時点におけるアーカイブ。 8 March 2008閲覧。

- ^ Eves, Howard W. (1969). In Mathematical Circles: A Selection of Mathematical Stories and Anecdotes. 3–4. Prindle, Weber and Schmidt. pp. 91–92

- ^ Riemann, Bernhard. 1867 [1854]. "On the hypotheses which lie at the bases of geometry" (Habilitationsschrift)のクリフォードによる翻訳。 – トリニティ・カレッジ数学学校

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1873. "On the hypotheses which lie at the bases of geometry." Nature 8:14–17, 36–37.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1882. "Paper #9." P. 55–71 in Mathematical Papers.

- ^ Biggs, Norman L.; Lloyd, Edward Keith; Wilson, Robin James (1976). Graph Theory: 1736-1936. Oxford University Press. p. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-853916-2

- ^ Clifford, William (1878). “Applications of Grassmann's extensive algebra”. American Journal of Mathematics 1 (4): 350–358. doi:10.2307/2369379. JSTOR 2369379.

- ^ Hestenes. “On the Evolution of Geometric Algebra and Geometric Calculus”. 2024年12月24日閲覧。

- ^ Dechant, Pierre-Philippe (March 2014). “A Clifford algebraic framework for Coxeter group theoretic computations”. Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 14 (1): 89–108. arXiv:1207.5005. Bibcode: 2012arXiv1207.5005D. doi:10.1007/s00006-013-0422-4.

- ^ Frontispiece of Lectures and Essays by the Late William Kingdon Clifford, F.R.S., vol 2.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1878. "On the Nature of Things-in-Themselves." Mind 3(9):57–67. doi:10.1093/mind/os-3.9.57. JSTOR 2246617.

- ^ Clifford, C. K., and G. E. Berrios. 2000. "Body and Mind." History of Psychiatry 11(43):311–38. doi:10.1177/0957154x0001104305. PMID 11640231.

- ^ a b c d Clifford, William K. 1877. "The Ethics of Belief Archived 23 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine.." Contemporary Review 29:289.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1885. Common Sense of the Exact Sciences. London: Kegan Paul, Trench and Co. p. 214.

- ^ Frankland, William Barrett. 1910. Theories of Parallelism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–49.

- ^ Weyl, Hermann. 1923. Raum Zeit Materie. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 101

- ^ Bell, Eric Temple. 1940. The Development of Mathematics. pp. 359–60.

- ^ Wheeler, John Archibald. 1962 [1960]. "Curved empty space as the building material of the physical world: an assessment." In Logic, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science, edited by E. Nagel. Stanford University Press.

- ^ Whitrow, Gerald James. 1961. The Natural Philosophy of Time (1st ed.). pp. 246–47.—1980 [1961]. The Natural Philosophy of Time (2nd ed.). pp. 291.

- ^ Lanczos, Cornelius. 1970. Space Through the Ages: The Evolution of Geometrical Ideas from Pythagoras to Hilbert and Einstein. Academic Press. p. 222.

- ^ Hoffmann, Banesh. 1973. "Relativity." Dictionary of the History of Ideas 4:80. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ a b Farwell, Ruth, and Christopher Knee. 1990. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 21:91–121.

- ^ Farwell, Ruth, and Christopher Knee. 1992. "The Geometric Challenge of Riemann and Clifford." Pp. 98–106 in 1830–1930: A Century of Geometry, edited by L. Boi, D. Flament, and J. Salanskis. Lecture Notes in Physics 402. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-540-47058-8. doi:10.1007/3-540-55408-4_56.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1876 [1870]. "On the Space-Theory of Matter." Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 2:157–58. OCLC 6084206. OL 20550270M. proceedingscamb06socigoog - インターネット・アーカイブ

- ^ Clifford, William K. 2007 [1870]. "On the Space-Theory of Matter." P. 71 in Beyond Geometry: Classic Papers from Riemann to Einstein, edited by P. Pesic. Mineola: Dover Publications. Bibcode: 2007bgcp.book...71K .

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1886 [1877]. "The Ethics of Belief" (full text). Lectures and Essays (2nd ed.), edited by L. Stephen and F. Pollock. Macmillan and Co. – via A. J. Burger (2008).

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1878. Elements of Dynamic: An Introduction to the Study of Motion And Rest In Solid And Fluid Bodies I, II, & III. London: MacMillan and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1878. "Applications of Grassmann's Extensive Algebra." American Journal of Mathematics 1(4):353. doi:10.2307/2369379.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1879. Seeing and Thinking. London: Macmillan and Co.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1901 [1879]. Lectures and Essays I (3rd ed.), edited by L. Stephen and F. Pollock. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1881. "Mathematical Fragments" (facsimile). London: Macmillan Company. Located at University of Bordeaux. Science and Technology Library. FR 14652.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1882. Mathematical Papers, edited by R. Tucker, introduction by H. J. S. Smith. London: MacMillan and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1885. The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences, completed by K. Pearson. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, and Co.

- ^ Clifford, William K. 1996 [1887]. "Elements of Dynamic" 2. In From Kant to Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, edited by W. B. Ewald. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- ^ 『春宵十話』光文社、1963年2月、23頁。ISBN 978-4-334-74146-4。

-

この記事にはアメリカ合衆国内で著作権が消滅した次の百科事典本文を含む: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Clifford, William Kingdon". Encyclopædia Britannica (英語). Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 506.

この記事にはアメリカ合衆国内で著作権が消滅した次の百科事典本文を含む: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Clifford, William Kingdon". Encyclopædia Britannica (英語). Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 506.

参考文献

[編集]- Chisholm, M. (1997). “William Kingdon Clifford (1845-1879) and his wife Lucy (1846-1929)”. Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 7S: 27–41 22 April 2007閲覧。. (The on-line version lacks the article's photographs.)

- Chisholm, M. (2002). Such Silver Currents - The Story of William and Lucy Clifford, 1845-1929. Cambridge, UK: The Lutterworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7188-3017-5

- Farwell, Ruth; Knee, Christopher (1990). “The End of the Absolute: a nineteenth century contribution to General Relativity”. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 21 (1): 91–121. Bibcode: 1990SHPSA..21...91F. doi:10.1016/0039-3681(90)90016-2.

- Macfarlane, Alexander (1916). Lectures on Ten British Mathematicians of the Nineteenth Century. New York: John Wiley and Sons. "Lectures on Ten British Mathematicians of the Nineteenth Century." (See especially pages 78–91)

- Madigan, Timothy J. (2010). W.K. Clifford and "The Ethics of Belief Cambridge Scholars Press, Cambridge, UK 978-1847-18503-7.

- Penrose, Roger (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780679454434 (See especially Chapter 11)

- Stephen, Leslie; Pollock, Frederick (1879). Lectures and Essays by the Late William Kingdon Clifford, F.R.S. 1. New York: Macmillan and Company

- Stephen, Leslie; Pollock, Frederick (1879). Lectures and Essays by the Late William Kingdon Clifford, F.R.S. 2. New York: Macmillan and Company

外部リンク

[編集]- ウィリアム・キングドン・クリフォードの作品 (インターフェイスは英語)- プロジェクト・グーテンベルク

- William and Lucy Clifford (with pictures)

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “William Kingdon Clifford”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- ウィリアム・キングドン・クリフォードに関連する著作物 - インターネットアーカイブ

- William Kingdon Cliffordの著作 - LibriVox(パブリックドメインオーディオブック)

- Clifford, William Kingdon, William James, and A.J. Burger (Ed.), The Ethics of Belief.

- Joe Rooney William Kingdon Clifford, Department of Design and Innovation, the Open University, London.