E-セレクチン

E-セレクチン(英: E-selectin)は、細胞接着分子セレクチンの1種であり、サイトカインによって活性化された血管内皮細胞で発現する。CD62E(CD62 antigen-like family member E)、ELAM-1(endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1)、LECAM2(leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 2)としても知られる。他のセレクチンと同様、炎症に重要な役割を果たす。ヒトでは、E-セレクチンはSELE遺伝子にコードされている[5]。

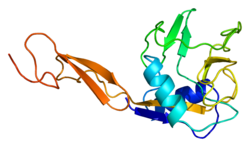

構造

[編集]E-セレクチンは、N末端のC型レクチンドメイン、EGF様ドメイン、6つのSushiドメイン(SCRリピート)、膜貫通ドメイン(TM)、細胞内の細胞質テール(cyto)から構成される。ヒトのE-セレクチンのリガンド結合領域(C型レクチンドメインとEGF様ドメイン)の構造は、1994年に2.0 Åの分解能で決定されている[6]。その構造からは、2つのドメイン間の限定的な接触と、他のC型レクチンからは予想されていなかった様式でのカルシウムイオンの配位が明らかにされた。構造機能解析からは、リガンド結合に関与している可能性のある領域とアミノ酸側鎖が特定された。シアリルルイスX(SLeX、NeuNAcα2,3Galβ1,4[Fucα1,3]GlcNAc)四糖と結合したE-セレクチンの構造は2000年に解かれた[7]。

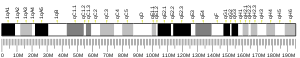

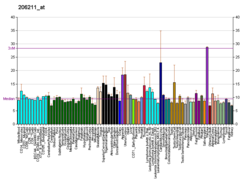

遺伝子と調節

[編集]ヒトでは、E-セレクチンはSELE遺伝子にコードされている。C型レクチンドメイン、EGF様ドメイン、SCRリピート、膜貫通ドメインはそれぞれ別個のエクソンにコードされており、細胞質ドメインは2つのエクソンからなる。1番染色体上のE-セレクチンの遺伝子座はL-セレクチンの遺伝子座と隣接している[8]。

バイベル・パラーデ小体と呼ばれる小胞に貯蔵されているP-セレクチンとは異なり、E-セレクチンは細胞内に貯蔵されず、細胞表面での発現には転写、翻訳、そして表面への輸送が必要となる。E-セレクチンの産生はP-セレクチンの発現によって刺激され、P-セレクチンはTNFα、IL-1、リポ多糖によって刺激される[9][10]。サイトカインの認識後、E-セレクチンが血管内皮細胞の表面に発現するまでには約2時間かかる。E-セレクチンの発現はサイトカインによる刺激から6–12時間後に最大となり、24時間以内に基底レベルへと戻る[10]。

ずり応力もE-セレクチンの発現に影響を与えることが知られている。強いせん断流は虚血再灌流障害時にみられるIL-1βに対する急性応答を亢進する一方、迅速にE-セレクチンをダウンレギュレーションして慢性的な炎症から保護する[11]。

ゲニステイン、ホルモノネチン、ビオカニンA、ダイゼインなど、エストロゲン様の生物学的活性を示す植物由来化合物であるフィトエストロゲンやそれらの混合物は、細胞表面や培養上清中のE-セレクチン、VCAM-1、ICAM-1の量を減少させることが判明している[12]。

リガンド

[編集]E-セレクチンは、特定の白血球の細胞表面タンパク質に存在するシアル化糖鎖を認識して結合する。E-セレクチンのリガンドは、好中球、単球、好酸球、エフェクターメモリーT細胞、ナチュラルキラー細胞に発現している。これらの細胞種はE-セレクチンの発現と関係して急性・慢性炎症部位に存在しており、そのためE-セレクチンがこれらの細胞を炎症部位へリクルートしていることが示唆されている。

リガンドとなる糖鎖には、単球、顆粒球、T細胞に存在するルイスX、ルイスAファミリーのメンバーがある[13]。

好中球と骨髄性細胞に存在する糖タンパク質ESL-1は、最初に記載されたE-セレクチンのカウンターレセプターである。ESL-1は受容体型チロシンキナーゼであるFGF受容体のバリアントであり、E-セレクチンへの結合は細胞内でのシグナル伝達の開始に関与している可能性がある[14]。ヒト好中球のPSGL-1も、内皮に発現したE-セレクチンの流動条件下での高効率なリガンドである[15]。PSGL-1は、炎症組織の周囲の活性化内皮での白血球のローリングを媒介する。ESL-1とPSGL-1はどちらもE/P-セレクチンと結合するためのシアリルルイスA/Xを持っている[16]。E-セレクチンは腫瘍細胞上のリガンドと結合し、腫瘍細胞の内皮細胞への接着を媒介することが知られており、E-セレクチンのリガンドはがんの転移に関与している。ESL-1やPSGL-1のin vivoでの転移における役割は確立されておらず、明確な実証はなされていないものの、骨に転移した前立腺がん細胞の表面でPSGL-1が検出されていることから、PSGL-1が前立腺がん細胞の骨への浸潤に関与している可能性が示唆されている[17]。

がん細胞のE-セレクチンリガンドとしては、結腸がん細胞上のCD44、DR3、LAMP1、LAMP2[18]、乳がん細胞上のCD44v、Mac2-BP、ガングリオシドなどが同定されている[19][20][21]。

ヒトの好中球では、スフィンゴ糖脂質NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCerとその類縁構造がE-セレクチンの機能的なレセプターである[22]。

機能

[編集]炎症における役割

[編集]E-セレクチンは、炎症時に損傷部位への白血球のリクルートに重要な役割を果たす。炎症組織におけるマクロファージによるIL-1とTNF-αの局所的な放出は、近接する血管内皮細胞でE-セレクチンの過剰発現を誘導する[23]。適切なリガンドを発現している血中の白血球は、血流によるずり応力下でもE-セレクチンに対して低い親和性で結合し、一過的な相互作用の形成と崩壊によって血管の内壁に沿って「ローリング」する。

炎症反応が進行すると、損傷組織から放出されたケモカインが血管に進入してローリングしている白血球を活性化し、白血球は内皮表面への強固な結合が可能となって組織への進入が開始される[13]。

P-セレクチンも同様の機能を持つが、P-セレクチンは必要に応じて合成されるのではなく細胞内に貯蔵されているため、数分以内に内皮細胞表面に発現する[13]。

がんにおける役割

[編集]E-セレクチンは、炎症刺激時に内皮細胞に誘導され、単球やHL60白血病細胞の接着を媒介する膜貫通受容体として最初に発見された[24][25]。このことから、がん細胞はIL-1βやTNF-αなどの炎症性サイトカインを分泌し、離れた転移部位でE-セレクチンを誘導する、という仮説が提唱された。この誘導により、循環腫瘍細胞は刺激された部位で停止し、活性化された内皮に沿ってローリングし、血管外に出て転移を行うことができるようになると考えらえている[26]。その後の研究により、結腸がん細胞へのE-セレクチンの結合は転移能の増加と相関していること[27]、複数のタイプのがん細胞が通常は免疫細胞に発現している糖タンパク質や糖脂質のリガンドを利用してE-セレクチンに結合していることが示された[28][29]。さらに、せん断流条件下では、がん細胞はE-セレクチンと最初に結合するという結合機構のカスケードが研究から示されている。がん細胞はまずE-セレクチンと結合することでマジックテープのような相互作用を形成し、その後により親和性の高いインテグリンと結合することで、腫瘍細胞と活性化した内皮との間に強固な結合が形成される[30][31]。

In vitroでのデータや臨床的な証拠の多くがE-セレクチンを介したがん転移仮説を支持している一方で、がんの転移に関するin vivoでの研究では、E-セレクチンのノックアウトが白血病細胞注入直後の骨への接着へ与える影響はわずかなものであること[32]、実験的な肺への転移はE-セレクチンの遺伝的欠失の影響を受けないことが示されている[33][34]。このパラドックスは、E-セレクチンは骨髄の内皮細胞では恒常的に発現しているだけであり[35]、そこで造血に重要な役割を果たしていると考えられるが[36]、 E-セレクチンを介した下流経路の活性化は結合の30時間後に生じ、またE-セレクチンは骨へ転移する細胞にハイジャックされるが他の部位では起こらないためであると考えられる[37]。このデータは、E-セレクチン阻害剤を用いて乳がんの骨転移を抑制するという、現在進行中の臨床研究を裏付けるものでもある[38]。E-セレクチンのリガンドの生物学は複雑であり、さまざまながん細胞で少なくとも15種類の糖タンパク質や糖脂質Eが-セレクチンの基質となることが記載されているが、骨転移を媒介することが示されたのは糖タンパク質GLG1(ESL-1)のみであった[37]。リガンドやその組み合わせによって、がんの転移の機構は異なると考えられる。また、E-セレクチンノックアウトマウスでは原発巣での腫瘍の成長が増大することも示されている[39][40]。

腫瘍細胞から局所的に分泌されたサイトカインに応答したE-セレクチンの誘導は、腫瘍細胞との直接的な相互作用だけでなく、抗がん剤を内包したSLeX結合ナノ粒子やチオアプタマーの腫瘍特異的な標的化を可能にする[41]。さらに、E-セレクチンは単球を原発巣や肺転移巣にリクルートし、炎症性の腫瘍微小環境を促進する機能を有する可能性がある[42]。こうした相互作用の遮断や、CAR-T細胞のE-セレクチン陽性部位への輸送が可能になれば、将来的な治療法の開発につながる可能性がある。

病理との関係

[編集]重症疾患多発ニューロパチー

[編集]敗血症などで血糖値が上昇した場合には、E-セレクチンの発現は正常よりも高くなり、微小血管の透過性が高くなる。透過性の増大は骨格筋の血管内皮の浮腫をもたらし、骨格筋の虚血(血液供給の制限)と最終的には壊死(細胞死)が引き起こされる。この機構は重症疾患多発ニューロパチー・ミオパチー(CIPNM)の原因となる病理である[43]。ベルベリンなどの伝統中国医学の薬剤はE-セレクチンをダウンレギュレーションする[44]。

病原体の接着

[編集]ヒト臍帯静脈内皮細胞(HUVEC)へのジンジバリス菌Porphyromonas gingivalisの接着は、TNF-αによるE-セレクチンの誘導によって増大することが示されている。E-セレクチンやシアリルルイスXに対する抗体は、TNF-αで刺激されたHUVECへのP. gingivalisの接着を抑制する。OmpA様タンパク質Pgm6/7を欠く変異型P. gingivalisは刺激されたHUVECへの接着が減少するが、線毛を欠損した変異体は影響を受けない。E-セレクチンを介したP. gingivalisの接着は内皮細胞のエキソサイトーシスを活性化する。これらの結果からは、宿主のE-セレクチンと病原体のPgm6/7の相互作用がP. gingivalisの内皮細胞への接着を媒介し、血管の炎症を開始している可能性が示唆される[45]。

急性冠症候群

[編集]急性冠症候群(ACS)患者の脆弱なプラークの内膜では、E-セレクチンとPECAM-1の発現が免疫組織化学的に大きく増加しており、特に新生血管の内皮細胞で顕著であった。また、PECAM-1とE-セレクチンの発現は炎症性細胞の密度と正の相関があり、炎症反応と脆弱なプラークの形成に重要な役割を果たしている可能性が示唆された。E-セレクチンのSer128Arg多型はACSと関連しており、ACSの危険因子である可能性がある[46]。

ニコチンを介した誘導

[編集]喫煙は血管内皮の機能不全を誘導し、アテローム性動脈硬化の可能性の増加と強く関連している。内皮細胞では、たばこの煙に含まれる依存性成分であるニコチンへの曝露によって、E-セレクチンなどさまざまな細胞接着分子がアップレギュレーションされることが示されている。ニコチン刺激による単球の内皮細胞への接着は、α7-nAChR、β-Arr1の活性化とc-Srcによって調節されるE2F1を介したE-セレクチン遺伝子の転写の増加に依存している。したがって、RRD-251などE2F1の活性を標的とする薬剤は喫煙を原因とするアテローム性動脈硬化の治療に有用である可能性がある[47]。

脳動脈瘤

[編集]ヒトの破裂した脳動脈瘤の組織では、E-セレクチンの発現が増加していることも判明している。E-セレクチンは炎症を促進して脳動脈壁を弱め、脳動脈瘤の形成や破裂の過程に関与する重要な因子である可能性がある[48]。

バイオマーカーとして

[編集]E-セレクチンは、大腸がんなどいくつかのがんの転移や再発のバイオマーカーとしても注目されている[49]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000007908 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026582 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Structure and chromosomal location of the gene for endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 266 (4): 2466–73. (February 1991). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)52267-5. PMID 1703529.

- ^ “Insight into E-selectin/ligand interaction from the crystal structure and mutagenesis of the lec/EGF domains”. Nature 367 (6463): 532–8. (February 1994). Bibcode: 1994Natur.367..532G. doi:10.1038/367532a0. PMID 7509040.

- ^ “Insights into the molecular basis of leukocyte tethering and rolling revealed by structures of P- and E-selectin bound to SLe(X) and PSGL-1”. Cell 103 (3): 467–79. (October 2000). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00138-0. PMID 11081633.

- ^ Cummings RD (2008). “Selectins”. Essentials of Glycobiology (2nd ed.). Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-770-9

- ^ Janeway C (2005). Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-4101-6

- ^ a b “E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are released by activated human endothelial cells in vitro”. Immunology 77 (4): 543–9. (December 1992). PMC 1421640. PMID 1283598.

- ^ “Shear stress modulation of IL-1β-induced E-selectin expression in human endothelial cells”. PLOS ONE 7 (2): e31874. (2012). Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...731874H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031874. PMC 3286450. PMID 22384091.

- ^ “Effects of phytoestrogens derived from soy bean on expression of adhesion molecules on HUVEC”. Climacteric 15 (2): 186–94. (April 2012). doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.582970. PMID 22066752.

- ^ a b c Robbins pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. (1999). ISBN 0-7216-7335-X

- ^ Steegmaier, M.; Levinovitz, A.; Isenmann, S.; Borges, E.; Lenter, M.; Kocher, H. P.; Kleuser, B.; Vestweber, D. (1995-02-16). “The E-selectin-ligand ESL-1 is a variant of a receptor for fibroblast growth factor”. Nature 373 (6515): 615–620. doi:10.1038/373615a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 7531823.

- ^ “PSGL-1 derived from human neutrophils is a high-efficiency ligand for endothelium-expressed E-selectin under flow”. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 289 (2): C415-24. (August 2005). doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00289.2004. PMID 15814589.

- ^ “Carbohydrate-mediated cell adhesion in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis”. Cancer Science 95 (5): 377–84. (May 2004). doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03219.x. PMID 15132763.

- ^ “Identification of leukocyte E-selectin ligands, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and E-selectin ligand-1, on human metastatic prostate tumor cells”. Cancer Research 65 (13): 5750–60. (July 2005). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4653. PMC 1472661. PMID 15994950.

- ^ “Selectins and selectin ligands in extravasation of cancer cells and organ selectivity of metastasis”. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis 25 (4): 335–44. (2008). doi:10.1007/s10585-007-9096-4. PMID 17891461.

- ^ “CD44 variant isoforms expressed by breast cancer cells are functional E-selectin ligands under flow conditions”. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 308 (1): C68-78. (January 2015). doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00094.2014. PMC 4281670. PMID 25339657.

- ^ “Mac-2 binding protein is a novel E-selectin ligand expressed by breast cancer cells”. PLOS ONE 7 (9): e44529. (2012). Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...744529S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044529. PMC 3435295. PMID 22970241.

- ^ “Gangliosides expressed on breast cancer cells are E-selectin ligands”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 406 (3): 423–9. (March 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.061. PMID 21329670.

- ^ “E-selectin receptors on human leukocytes”. Blood 112 (9): 3744–52. (November 2008). doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-149641. PMC 2572800. PMID 18579791.

- ^ Murphy, Kenneth (2012). Janeway's immunobiology. Paul Travers, Mark Walport, Charles Janeway (8th ed ed.). New York: Garland Science. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8153-4243-4. OCLC 733935898

- ^ “Identification of an inducible endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84 (24): 9238–42. (December 1987). Bibcode: 1987PNAS...84.9238B. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.24.9238. PMC 299728. PMID 2827173.

- ^ “Recognition by ELAM-1 of the sialyl-Lex determinant on myeloid and tumor cells”. Science 250 (4984): 1132–5. (November 1990). Bibcode: 1990Sci...250.1132W. doi:10.1126/science.1701275. PMID 1701275.

- ^ “Rapid induction of cytokine and E-selectin expression in the liver in response to metastatic tumor cells”. Cancer Research 59 (6): 1356–61. (March 1999). PMID 10096570.

- ^ “Differential E-selectin-dependent adhesion efficiency in sublines of a human colon cancer exhibiting distinct metastatic potentials”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 269 (2): 1425–31. (January 1994). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)42275-7. PMID 7507108.

- ^ “Rolling of human bone-metastatic prostate tumor cells on human bone marrow endothelium under shear flow is mediated by E-selectin”. Cancer Research 64 (15): 5261–9. (August 2004). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0691. PMID 15289332.

- ^ “Adhesion of HT-29 colon carcinoma cells to endothelial cells requires sequential events involving E-selectin and integrin beta4”. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis 21 (3): 257–64. (2004). doi:10.1023/B:CLIN.0000037708.09420.9a. PMID 15387376.

- ^ “Definition of molecular determinants of prostate cancer cell bone extravasation”. Cancer Research 73 (2): 942–52. (January 2013). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3264. PMC 3548951. PMID 23149920.

- ^ “Targeting tumor-stromal interactions in bone metastasis”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 141 (2): 222–33. (February 2014). doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.10.006. PMC 3947254. PMID 24140083.

- ^ “In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment”. Nature 435 (7044): 969–73. (June 2005). Bibcode: 2005Natur.435..969S. doi:10.1038/nature03703. PMC 2570168. PMID 15959517.

- ^ “Selectins as mediators of lung metastasis”. Cancer Microenvironment 3 (1): 97–105. (February 2010). doi:10.1007/s12307-010-0043-6. PMC 2990482. PMID 21209777.

- ^ “Bone vascular niche E-selectin induces mesenchymal-epithelial transition and Wnt activation in cancer cells to promote bone metastasis”. Nature Cell Biology 21 (5): 627–639. (May 2019). doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0309-2. PMC 6556210. PMID 30988423.

- ^ “Dormant breast cancer micrometastases reside in specific bone marrow niches that regulate their transit to and from bone”. Science Translational Medicine 8 (340): 340ra73. (May 2016). doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad4059. PMID 27225183.

- ^ “Vascular niche E-selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance”. Nature Medicine 18 (11): 1651–7. (November 2012). doi:10.1038/nm.2969. PMID 23086476.

- ^ a b “Bone vascular niche E-selectin induces mesenchymal-epithelial transition and Wnt activation in cancer cells to promote bone metastasis”. Nature Cell Biology 21 (5): 627–639. (May 2019). doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0309-2. PMC 6556210. PMID 30988423.

- ^ “GlycoMimetics Announces Plans to Initiate Breast Cancer Trial to Evaluate GMI-1359” (英語). www.businesswire.com (2019年4月12日). 2019年6月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Bone vascular niche E-selectin induces mesenchymal-epithelial transition and Wnt activation in cancer cells to promote bone metastasis”. Nature Cell Biology 21 (5): 627–639. (May 2019). doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0309-2. PMC 6556210. PMID 30988423.

- ^ “Increased primary tumor growth in mice null for beta3- or beta3/beta5-integrins or selectins”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (3): 763–8. (January 2004). Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101..763T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307289101. PMC 321755. PMID 14718670.

- ^ “Bone marrow endothelium-targeted therapeutics for metastatic breast cancer”. Journal of Controlled Release 187: 22–9. (August 2014). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.04.057. PMC 4109393. PMID 24818768.

- ^ “Selectin-mediated activation of endothelial cells induces expression of CCL5 and promotes metastasis through recruitment of monocytes”. Blood 114 (20): 4583–91. (November 2009). doi:10.1182/blood-2008-10-186585. PMID 19779041.

- ^ “Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: clinical features, risk factors and prognosis”. European Journal of Neurology 13 (11): 1203–12. (November 2006). doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01498.x. PMID 17038033.

- ^ “Chinese herbal medicinal ingredients inhibit secretion of IL-6, IL-8, E-selectin and TXB2 in LPS-induced rat intestinal microvascular endothelial cells”. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology 31 (4): 550–5. (2009). doi:10.3109/08923970902814129. PMID 19874221.

- ^ “E-selectin mediates Porphyromonas gingivalis adherence to human endothelial cells”. Infection and Immunity 80 (7): 2570–6. (July 2012). doi:10.1128/IAI.06098-11. PMC 3416463. PMID 22508864.

- ^ “[PECAM-1 and E-selectin expression in vulnerable plague and their relationships to myocardial Leu125Val polymorphism of PECAM-1 and Ser128Arg polymorphism of E-selectin in patients with acute coronary syndrome]” (中国語). Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 39 (12): 1110–6. (December 2011). PMID 22336504.

- ^ “Nicotine-mediated induction of E-selectin in aortic endothelial cells requires Src kinase and E2F1 transcriptional activity”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 418 (1): 56–61. (February 2012). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.127. PMC 3273677. PMID 22240023.

- ^ “E-selectin expression increased in human ruptured cerebral aneurysm tissues”. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 38 (6): 858–62. (November 2011). doi:10.1017/s0317167100012439. PMID 22030423.

- ^ “Significance of serum concentrations of E-selectin and CA19-9 in the prognosis of colorectal cancer”. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology 40 (11): 1073–80. (November 2010). doi:10.1093/jjco/hyq095. PMID 20576794.

外部リンク

[編集]- E-Selectin - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス