脊髄刺激装置

| 脊髄刺激装置 | |

|---|---|

| 治療法 | |

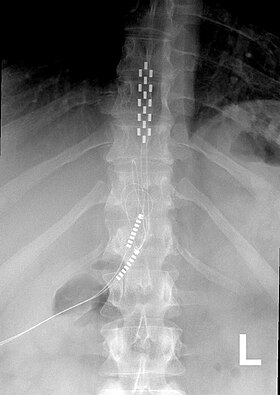

胸椎に植え込まれた脊髄刺激装置(SCS)の前方視X線写真 |

脊髄刺激装置(せきずいしげきそうち、spinal cord stimulator, SCS)または背柱刺激装置(せきちゅうしげきそうち、dorsal column stimulator, DCS)は、埋め込み型神経調節装置(「疼痛ペースメーカー」と呼ばれることもある)の一種である。

概要

[編集]特定の疼痛状態の治療のために電気信号を脊髄の選択領域(脊髄後柱)に送信するために使用される。

SCSは、保存的な治療に反応しない疼痛状態にある人に考慮される[1]。また、脊髄損傷患者が硬膜外電気刺激(EES)を介して再び歩けるようにすることを目指す脊髄刺激装置も研究開発中である[2][3]。

適応

[編集]SCSの最も一般的な適応は、米国では背部手術失敗症候群(FBSS)であり、ヨーロッパでは末梢性虚血性疼痛である[4][5]。日本では、「薬物療法、他の外科療法及び神経ブロック療法の効果が認められない慢性難治性疼痛の除去又は軽減」が適応である[6]。

2014年の時点で、米国食品医薬品局はFBSS、慢性疼痛、複合性局所疼痛症候群、難治性狭心症、腹部および会陰の内臓痛[1]および神経損傷による四肢の痛みの治療としてSCSを承認した[7]。

患者が心理的評価を受け、SCSの適切な候補者であると判断されたら、最適な刺激パターンを決定するためにトライアルと呼ばれる一時的なSCSが留置され、外部パルス発生器と共に3~10日間自宅に帰される(海外の場合)。日本ではトライアル期間は入院を継続することが多いであろう[8]。痛みのコントロールと身体活動性の向上が達成された場合は、リード(脊髄刺激の導線、日本でもリードと呼称されることが多い)とパルスジェネレータ(電気信号発生器、日本でも外来語としてパルスジェネレータと呼ばれることが多い)を備えた恒久的なSCS装置が留置される[9]。

禁忌

[編集]SCS は、凝固関連の障害がある人、または抗凝固療法を受けている人には禁忌となる場合がある[1]。その他の禁忌には、局所および全身の感染症、ペースメーカー、または手術前の画像検査で留置が困難な解剖学的構造があることが示されている人、または心理的評価中に懸念が生じた場合が含まれる[10][11][12]。

副作用と合併症

[編集]SCSの合併症は、単純で簡単に修正できる問題から、壊滅的な麻痺、神経損傷、死亡にまで及ぶ。7年間の追跡調査では、全体的な合併症率は5~18%であった。最も一般的な合併症には、リードのずれ、リードの破損、および感染が含まれる。その他の合併症には、パルスジェネレータの回転、血腫(皮下または硬膜外)、脳脊髄液漏出、硬膜穿刺後の頭痛、パルスジェネレータ部位の不快感、漿液腫、一過性対麻痺などがある[13]。

旧型SCSによるピリピリした感覚を不快に感じる事例もある。

最も一般的なハードウェア関連の合併症はリードのずれ、であり、埋め込まれた電極が元の配置からずれる。この合併症では、再プログラミングにより、知覚異常に対する治療範囲を再認識させることができる[14]。大きなリードのずれを伴う状況では、リードの配置をリセットするために再手術が必要になる場合がある[15]。リードがずれた人の割合の報告は研究によって大きく異なるが、大半の研究では、脊髄刺激によるリードのずれは10~25%の範囲で報告されている[15]。

作用機序

[編集]脊髄刺激の作用の神経生理学的メカニズムは完全には理解されていないが、中枢神経系の痛みの処理を変化させることにより、疼痛感覚をピリピリすることでマスクしている可能性があるとされる[16]。神経因性疼痛にSCSを適用した場合の鎮痛メカニズムは、四肢虚血による鎮痛に関与するメカニズムとは大きく異なる可能性がある[17][18]。神経障害性疼痛状態では、SCSによって後角が局所神経学的に変化してニューロンの過興奮を抑制することが実験により明らかにされている。具体的には、GABA分泌とセロトニンの濃度上昇、およびおそらくグルタミン酸やアスパラギン酸を含むいくつかの興奮性アミノ酸の濃度の低下に関するエビデンスが幾つかある。虚血性疼痛の場合、鎮痛は酸素需要供給の回復に由来するようである。この効果は、交感神経系の抑制によって媒介される可能性があるが、血管拡張の可能性もある。また、上記の2つの機序の組み合わせが関与している可能性もある[19]。

外科的処置

[編集]脊髄刺激装置は、2つの異なる段階で留置される: 試用段階とそれに続く最終埋込段階である。まず、無菌的に皮膚を消毒し、ドレープで被覆する。硬膜外腔には、14ゲージのTuohy針を使用した抵抗消失法で到達する。リードは、適切な脊椎レベルまで透視ガイドで慎重に送り込まれる。この手順を繰り返して、最初のリードに隣接して別のリードを配置する。透視検査は、SCSリードの適切な配置を確認するために、手技中に頻繁に行われる。リードの配置は、患者の痛みの場所によって異なる。以前の研究に基づいて、腰痛患者のリード配置は通常T9からT10である。その後、技師が、通常、非常に低い周波数から始まる刺激を開始する。患者は、リード線の活性化によって知覚される感覚を説明するよう促され、技師は、患者の標的疼痛部位の知覚範囲が最大となるようにSCSを較正する。最後に、リード線が移動する危険を減らすために外部に固定され、手術部位が洗浄され、清潔なドレッシングが皮膚に貼り付けられる。患者が処置から回復した後、装置は再びテストされ、プログラムされる[20]。

患者スクリーニング

[編集]刺激装置の留置の候補である患者は、禁忌および併存疾患についてスクリーニングする必要がある。刺激装置試験の前に、以下を考慮する必要がある:[1]

- 出血のリスク – 脊髄刺激装置の治験および移植は、永久的な神経学的損傷を引き起こす可能性のある重篤な脊髄内出血のリスクが高い処置であることが確認されている。刺激装置の設置に先立ち,抗血小板薬および抗凝固薬の中止と再投与に関する適切な計画が必要である。

- 心理的評価 - うつ病、不安、身体化、および心気症は、脊髄刺激装置のより悪い結果と関連している。専門家は配置前の心理的評価を推奨している。精神障害の診断は、刺激装置の配置に対する厳密な禁忌ではない。ただし、試験配置を検討する前に障害の治療が必要である。

- SCS留置の遅れ – 慢性疼痛の発症後何年も経ってから刺激装置を留置すると、効果が低下する可能性がある。400例を対象としたレビューでは、痛みの発症から2年以内にSCS留置を受けた患者の成功率が85%近くであるのに対し、痛みの発症後15年以上経過してからSCSを留置した患者の成功率はわずか9%であった。[21]

- 技術的な困難 – 先天性か後天性であれ、解剖学的構造の違いにより、特定の個人では留置がうまくいかない場合がある。脊椎の画像診断は、刺激装置の留置よりも脊椎手術がより適切な患者の選択を導くために必要である。

トライアル期間

[編集]恒久留置前に脊髄刺激装置の有効性を評価するために、試験留置(トライアル)を実施する必要がある。この試験は、一時的なリードを硬膜外腔に配置し、経皮的に外部ジェネレーターに接続することから始まる。トライアルは通常3~7日間続き、その後SCS留置の前に2週間の猶予があり、トライアルによる感染がないことを確認する[15][22]。トライアルの成功とは、痛みの少なくとも50%の軽減と、元の痛みの領域の80%の感覚が変化することと定義される。患者の痛みが突然変化した場合は、リードの移動や刺激装置の誤動作の可能性について、さらなる調査が必要である[11]。

歴史

[編集]神経刺激による痛みの電気療法は、メルザックとウォールが1965年にゲートコントロール理論を提唱した直後に始まった。この理論は、痛みを伴う末梢刺激を伝達する神経と、触覚および振動感覚を伝達する神経の両方が、脊髄の後角(ゲート)で終結することを提唱した[23]。後者への入力を操作して、前者への「ゲートを閉じる」ことができるという仮説が立てられた。ゲート制御理論の応用として、Shealyら[24]は、慢性疼痛の治療のために最初の脊髄刺激装置を脊髄後柱に直接埋め込み、1971年にShimogiと同僚が硬膜外脊髄刺激の鎮痛特性を最初に報告した。それ以来、この技術は数多くの技術的および臨床的発展を遂げてきた。

現時点では、痛みの治療のための神経刺激は、神経刺激、脊髄刺激、脳深部刺激、および運動皮質刺激などが用いられている。

研究

[編集]SCSは、パーキンソン病[25]および狭心症の患者で研究されている[26]。

機器とソフトウェアの改善に関する研究には、電池寿命を延ばすための努力、閉ループ制御を開発するための努力、および刺激と体内埋め込み型薬物注入システムとの組み合わせ、などがある[25]。

SCSは、脊髄損傷を治療するためにも研究されている。2018年8月、欧州委員会のHorizon 2020 Future and Emerging Technologiesプログラムは、脊髄を「再配線」するように設計されたSCSのプロトタイプを構築している4カ国プロジェクトチームに350万ドルの資金援助を発表した[27][28]。2018年9月、Mayo ClinicとUCLAは、理学療法でサポートされている脊髄刺激が、麻痺のある人が補助下で立ったり歩いたりする能力を回復するのに役立つことを報告した[29]。2019年12月、脊髄刺激の歴史における最初の二重盲検無作為対照試験がLancet Neurologyに掲載された[30]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c d McKenzie-Brown (November 1, 2016). “Spinal cord stimulation: Placement and management”. UptoDate. 2022年10月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Paralysed man with severed spine walks thanks to implant”. BBC News. (7 February 2022) 10 March 2022閲覧。

- ^ Rowald, Andreas; Komi, Salif; Demesmaeker, Robin; Baaklini, Edeny; Hernandez-Charpak, Sergio Daniel; Paoles, Edoardo; Montanaro, Hazael; Cassara, Antonino et al. (February 2022). “Activity-dependent spinal cord neuromodulation rapidly restores trunk and leg motor functions after complete paralysis” (英語). Nature Medicine 28 (2): 260–271. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01663-5. ISSN 1546-170X.

- ^ Eldabe, Sam; Kumar, Krishna; Buchser, Eric; Taylor, Rod S. (July 2010). “An analysis of the components of pain, function, and health-related quality of life in patients with failed back surgery syndrome treated with spinal cord stimulation or conventional medical management”. Neuromodulation 13 (3): 201–209. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2009.00271.x. PMID 21992833.

- ^ Turner, J. A.; Loeser, J. D.; Bell, K. G. (December 1995). “Spinal cord stimulation for chronic low back pain: a systematic literature synthesis”. Neurosurgery 37 (6): 1088–1095; discussion 1095–1096. doi:10.1097/00006123-199512000-00008. PMID 8584149.

- ^ “K190 脊髄刺激装置植込術| 今日の臨床サポート - 最新のエビデンスに基づいた二次文献データベース.疾患・症状情報”. clinicalsup.jp. 2022年10月30日閲覧。

- ^ Song, Jason J.; Popescu, Adrian; Bell, Russell L. (May 2014). “Present and potential use of spinal cord stimulation to control chronic pain”. Pain Physician 17 (3): 235–246. PMID 24850105.

- ^ “SCS(脊髄刺激療法)|脳神経外科|診療科|新武雄病院|一般社団法人 巨樹の会”. www.shintakeo-hp.or.jp. 2022年10月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Spinal Cord Stimulation Systems and Implantation” (英語). www.aans.org. 2021年5月6日閲覧。

- ^ Narouze, Samer; Benzon, Honorio T.; Provenzano, David A.; Buvanendran, Asokumar; De Andres, José; Deer, Timothy R.; Rauck, Richard; Huntoon, Marc A. (May 2015). “Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications: guidelines from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain”. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 40 (3): 182–212. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000223. PMID 25899949.

- ^ a b Deer, Timothy R.; Mekhail, Nagy; Provenzano, David; Pope, Jason; Krames, Elliot; Leong, Michael; Levy, Robert M.; Abejon, David et al. (August 2014). “The appropriate use of neurostimulation of the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system for the treatment of chronic pain and ischemic diseases: the Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee”. Neuromodulation 17 (6): 515–550; discussion 550. doi:10.1111/ner.12208. PMID 25112889.

- ^ Knezevic, Nebojsa N.; Candido, Kenneth D.; Rana, Shalini; Knezevic, Ivana (July 2015). “The Use of Spinal Cord Neuromodulation in the Management of HIV-Related Polyneuropathy”. Pain Physician 18 (4): E643–650. PMID 26218955.

- ^ Hayek, Salim M.; Veizi, Elias; Hanes, Michael (October 2015). “Treatment-Limiting Complications of Percutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulator Implants: A Review of Eight Years of Experience From an Academic Center Database”. Neuromodulation 18 (7): 603–608; discussion 608–609. doi:10.1111/ner.12312. PMID 26053499.

- ^ Eldabe, Sam; Buchser, Eric; Duarte, Rui V. (2016-02-01). “Complications of Spinal Cord Stimulation and Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Techniques: A Review of the Literature”. Pain Medicine 17 (2): 325–336. doi:10.1093/pm/pnv025. PMID 26814260.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Krishna; Buchser, Eric; Linderoth, Bengt; Meglio, Mario; Van Buyten, Jean-Pierre (January 2007). “Avoiding complications from spinal cord stimulation: practical recommendations from an international panel of experts”. Neuromodulation 10 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2007.00084.x. PMID 22151809.

- ^ Sinclair, Chantelle; Verrills, Paul; Barnard, Adele (2016-07-01). “A review of spinal cord stimulation systems for chronic pain”. Journal of Pain Research 9: 481–492. doi:10.2147/jpr.s108884. PMC 4938148. PMID 27445503.

- ^ Linderoth, B.; Foreman, R. D. (July 1999). “Physiology of spinal cord stimulation: review and update”. Neuromodulation 2 (3): 150–164. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1403.1999.00150.x. PMID 22151202.

- ^ Oakley, John C.; Prager, Joshua P. (2002-11-15). “Spinal cord stimulation: mechanisms of action”. Spine 27 (22): 2574–2583. doi:10.1097/00007632-200211150-00034. PMID 12435996.

- ^ Kunnumpurath, Sreekumar; Srinivasagopalan, Ravi; Vadivelu, Nalini (1 September 2009). “Spinal cord stimulation: principles of past, present and future practice: a review”. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 23 (5): 333–339. doi:10.1007/s10877-009-9201-0. PMID 19728120.

- ^ Barolat, G.; Massaro, F.; He, J.; Zeme, S.; Ketcik, B. (February 1993). “Mapping of sensory responses to epidural stimulation of the intraspinal neural structures in man”. Journal of Neurosurgery 78 (2): 233–239. doi:10.3171/jns.1993.78.2.0233. ISSN 0022-3085. PMID 8421206.

- ^ Kumar, Krishna; Hunter, Gary; Demeria, Denny (2006-03-01). “Spinal Cord Stimulation in Treatment of Chronic Benign Pain: Challenges in Treatment Planning and Present Status, a 22-Year Experience” (英語). Neurosurgery 58 (3): 481–496. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000192162.99567.96. ISSN 0148-396X.

- ^ Linderoth, Bengt; Foreman, Robert D (July 1999). “Physiology of Spinal Cord Stimulation: Review and Update”. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2 (3): 150–164. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1403.1999.00150.x. ISSN 1094-7159. PMID 22151202.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Daniel R.; McEntire, Dan M.; Hambsch, Zakary J.; Kerfeld, Mitchell J.; Smith, Tyler A.; Reisbig, Mark D.; Youngblood, Charles F.; Agrawal, Devendra K. (December 2015). “Therapeutic Basis of Clinical Pain Modulation”. Clinical and Translational Science 8 (6): 848–856. doi:10.1111/cts.12282. PMC 4641846. PMID 25962969.

- ^ Shealy, C. N.; Mortimer, J. T.; Reswick, J. B. (July 1967). “Electrical inhibition of pain by stimulation of the dorsal columns: preliminary clinical report”. Anesthesia and Analgesia 46 (4): 489–491. doi:10.1213/00000539-196707000-00025. PMID 4952225.

- ^ a b de Andrade, Emerson Magno; Ghilardi, Maria Gabriela; Cury, Rubens Gisbert; Barbosa, Egberto Reis; Fuentes, Romulo; Teixeira, Manoel Jacobsen; Fonoff, Erich Talamoni (January 2016). “Spinal cord stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review”. Neurosurgical Review 39 (1): 27–35; discussion 35. doi:10.1007/s10143-015-0651-1. PMID 26219854.

- ^ Taylor, Rod S.; De Vries, Jessica; Buchser, Eric; Dejongste, Mike J. L. (2009-03-25). “Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of refractory angina: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials”. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 9: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-9-13. PMC 2667170. PMID 19320999.

- ^ “Radical project aims to bridge spinal cord injuries and give patients control of their limbs”. Healthcare IT Australia. (2018年8月24日) 2018年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “European Commission funds $3.5 million to develop prototype implant that rewires a spinal cord”. Healthcare IT News. (2018年8月23日) 2018年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “Spinal cord stimulation, physical therapy help paralyzed man stand, walk with assistance”. ScienceDaily. (2018年9月24日) 2022年10月28日閲覧。

- ^ Nagy Mekhail, Robert M Levy, Timothy R Deer, Leonardo Kapural, Sean Li, Kasra Amirdelfan, Corey W Hunter, Steven M Rosen, Shrif J Costandi, Steven M Falowski, Abram H Burgher, Jason E Pope, Christopher A Gilmore, Farooq A Qureshi, Peter S Staats, James Scowcroft, Jonathan Carlson, Christopher K Kim, Michael I Yang, Thomas Stauss, Lawrence Poree, Dan Brounstein, Robert Gorman, Gerrit E. Gmel, Erin Hanson, Dean M. Karantonis, Abeer Khurram, Deidre Kiefer, Angela Leitner, Dave Mugan, Milan Obradovic, John Parker, Peter Single, Nicole Soliday (2020). “Long-term safety and efficacy of closed-loop spinal cord stimulation to treat chronic back and leg pain (Evoke): a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial”. The Lancet Neurology 19: 123-134. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30414-4.