ネプリライシン

ネプリライシン(英: neprilysin)は、ヒトではMME遺伝子にコードされる酵素である。Membrane metallo-endopeptidase(MME)、neutral endopeptidase(NEP)、cluster of differentiation 10(CD10)、common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen(CALLA)の名称でも知られる。ネプリライシンは亜鉛依存的なメタロプロテアーゼで、グルカゴン、エンケファリン、P物質、ニューロテンシン、オキシトシン、ブラジキニンなどのペプチドを疎水性残基のN末端側で切断する[5]。また、ネプリライシンはアミロイドβを分解する。アミロイドβの異常なフォールディングと神経組織での凝集は、アルツハイマー病の原因として示唆されている。ネプリライシンは膜タンパク質として合成され、ゴルジ体から細胞表面へ輸送された後、細胞外ドメインが切り離されることがある。

ネプリライシンはさまざまな組織で広く発現しているが、腎臓に最も豊富に存在する。急性リンパ性白血病(ALL)抗原としても一般的であり、ALLの診断の際に重要な細胞表面マーカーである。このタンパク質はプレB細胞型の白血病細胞に存在し、ALLの症例の85%を占める[5]。

ネプリライシン(CD10)を発現している造血前駆細胞は、リンパ球系の共通前駆細胞であると見なされている。このことは、これらの細胞がT細胞、B細胞、ナチュラルキラー細胞へ分化できることを意味している[6]。CD10は初期B細胞、プロB細胞、プレB細胞、そしてリンパ節の胚中心で発現しているため、血液学的診断に利用される[7]。CD10陽性となる血液疾患には、ALL、血管免疫芽球性T細胞リンパ腫、バーキットリンパ腫、急性期の慢性骨髄性白血病(90%)、びまん性大細胞型B細胞性リンパ腫、濾胞中心細胞リンパ腫(70%)、有毛細胞白血病(10%)、骨髄腫(一部)が含まれる。急性骨髄性白血病、慢性リンパ性白血病、マントル細胞リンパ腫、辺縁帯リンパ腫ではCD10陰性となる傾向にある。CD10はプレB細胞に由来する非T細胞性ALL細胞や、バーキットリンパ腫や濾胞性リンパ腫などの胚中心関連非ホジキンリンパ腫でみられるが、より成熟したB細胞に由来する白血病細胞やリンパ腫ではみられない[8]。

アミロイドβの調節

[編集]ネプリライシンを欠損したノックアウトマウスは、アルツハイマー病に似た行動障害と脳へのアミロイドβの蓄積を示し[9]、このタンパク質がアルツハイマー病の過程と関係していることの強い証拠となっている。ネプリライシンはアミロイドβの分解の律速段階であると考えられており[10]、治療標的となる可能性があると考えられている。ペプチドホルモンであるソマトスタチンなどの化合物が酵素の活性レベルを上昇させることが示されている[11]。加齢と関係したネプリライシンの減少は、酸化損傷によって説明されるかもしれない。酸化損傷はアルツハイマー病の原因因子であることが知られており、認知機能が正常な高齢者と比較して、アルツハイマー病患者では酸化したネプリライシンが高率で存在する[12]。

シグナル伝達ペプチド

[編集]

ネプリライシンは他の生化学的過程にも関係しており、腎臓と肺の組織で特に高度に発現している。ネプリライシンの阻害薬は鎮痛剤と高血圧治療薬を目的としてデザインされており、エンケファリン、P物質、エンドセリン、心房性ナトリウム利尿ペプチドなどのシグナル伝達ペプチドに対する活性を阻害することで作用する[13][14]。

ネプリライシンの発現とさまざまなタイプのがんとの関係が観察されているものの、ネプリライシンの発現と発がんの関係性についてはいまだ明確ではない。がんのバイオマーカーの研究においては、ネプリライシンはCD10またはCALLAと呼ばれることが多い。転移性の癌腫や一部の進行性メラノーマなど一部のタイプのがんでは、ネプリライシンが過剰発現している[15]。一方他のタイプのがん、特に肺がんでは、ネプリライシンはダウンレギュレーションされている。そのため、ボンベシン関連哺乳類ホモログなどの分泌ペプチドによる、がん細胞の自己分泌性成長促進シグナルを調節することができない[16]。一部の植物のエキス(Ceropegia rupicola、Ceropegia rupicola、コレウス・フォルスコリのメタノール抽出物、Pavetta longifloraの水抽出物)は、中性エンドペプチダーゼ(ネプリライシンもこれに含まれる)の酵素活性を阻害することが判明している[17]。

阻害薬

[編集]ネプリライシンの阻害薬は鎮痛剤と高血圧治療薬を目的としてデザインされており[13][14]、一部は心不全の治療を意図している[18]。

- サクビトリル・バルサルタン(Entresto/LCZ696): 心不全の患者でエナラプリルとの比較試験が行われている[18]。

- サクビトリル(AHU-377): サクビトリル/バルサルタンの構成成分であるプロドラッグ

- サクビトリラト(LBQ657): 活性型サクビトリル

- RB-101: エンケファリナーゼの阻害剤、研究で利用される。

- UK-414,495

- オマパトリラト: ネプリライシンとアンジオテンシン変換酵素の二重阻害剤、血管性浮腫の懸念のためFDAの承認を得られなかった。

- エカドトリル

- カンドキサトリル

他のネプリライシンとアンジオテンシン変換酵素/アンジオテンシン受容体の二重阻害剤も製薬企業による開発が行われている[19]。

免疫組織化学

[編集]CD10は臨床病理学で診断目的で利用されている。

リンパ腫と白血病

[編集]- 急性リンパ性白血病(ALL)細胞はCD10陽性(CD10+)である。

- 濾胞性リンパ腫(濾胞中心細胞リンパ腫)はCD10+である。

- バーキットリンパ腫細胞はCD10+である。

- CD10陽性びまん性大細胞型B細胞性リンパ腫(CD10+ DLBCL)[20]

- 血管免疫芽球性T細胞リンパ腫(AITL)はCD10+であり[25][26]、AITLは他のT細胞型リンパ腫(CD10−)から区別される[27]。

- 一部の良性T細胞はCD10+である場合がある[28]。

上皮腫瘍

[編集]- 淡明細胞型腎細胞癌(ccRCC)

- 膵臓腫瘍

- 皮膚腫瘍

- 尿路上皮腫瘍はCD10を発現する(42–67%)[33]。

- CD10の発現は膀胱の尿路上皮癌の悪性度とステージの高さと強く相関している。CD10は膀胱癌の進行と関係している可能性がある[34]。

他の腫瘍

[編集]出典

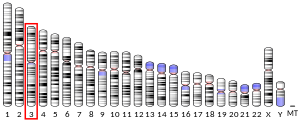

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000196549 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000027820 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ a b “Entrez Gene: Membrane metallo-endopeptidase”. 2020年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ Galy, Anne; Travis, Marilyn; Cen, Dazhi; Chen, Benjamin (Oct 1995). “Human T, B, natural killer, and dendritic cells arise from a common bone marrow progenitor cell subset.”. Immunity 3 (4): 459-473. doi:10.1016/1074-7613(95)90175-2. PMID 7584137.

- ^ Singh C (2011年2月25日). “CD10”. CD Markers. PathologyOutlines.com, Inc.. 2020年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Papandreou CN, Nanus DM (January 2010). “Is methylation the key to CD10 loss?”. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 32 (1): 2-3. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181c74aca. PMID 20051779.

- ^ Madani R, Poirier R, Wolfer DP, Welzl H, Groscurth P, Lipp HP, Lu B, El Mouedden M, Mercken M, Nitsch RM, Mohajeri MH (December 2006). “Lack of neprilysin suffices to generate murine amyloid-like deposits in the brain and behavioral deficit in vivo”. J. Neurosci. Res. 84 (8): 1871-1878. doi:10.1002/jnr.21074. PMID 16998901.

- ^ Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi M, Hosoki E, Kawashima-Morishima M, Lee HJ, Hama E, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Saido TC (February 2000). “Identification of the major Abeta1-42-degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition”. Nat. Med. 6 (2): 143–50. doi:10.1038/72237. PMID 10655101.

- ^ Iwata N, Higuchi M, Saido TC (November 2005). “Metabolism of amyloid-beta peptide and Alzheimer's disease”. Pharmacol. Ther. 108 (2): 129–148. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.03.010. PMID 16112736.

- ^ Wang DS, Iwata N, Hama E, Saido TC, Dickson DW (October 2003). “Oxidized neprilysin in aging and Alzheimer's disease brains”. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 310 (1): 236–241. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.003. PMID 14511676.

- ^ a b Sahli S, Stump B, Welti T, Schweizer WB, Diederich R, Blum-Kaelin D, Aebi JD, Böhm HJ (April 2005). “A New Class of Inhibitors for the Metalloprotease Neprilysin Based on a Central Imidazole Scaffold”. Helvetica Chimica Acta 88 (4): 707–730. doi:10.1002/hlca.200590050.

- ^ a b Oefner C, Roques BP, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Dale GE (February 2004). “Structural analysis of neprilysin with various specific and potent inhibitors”. Acta Crystallogr. D 60 (Pt 2): 392-396. doi:10.1107/S0907444903027410. PMID 14747736.

- ^ Velazquez EF, Yancovitz M, Pavlick A, Berman R, Shapiro R, Bogunovic D, O'Neill D, Yu YL, Spira J, Christos PJ, Zhou XK, Mazumdar M, Nanus DM, Liebes L, Bhardwaj N, Polsky D, Osman I (2007). “Clinical relevance of neutral endopeptidase (NEP/CD10) in melanoma”. J Transl Med 5 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-5-2. PMC 1770905. PMID 17207277.

- ^ Cohen AJ, Bunn PA, Franklin W, Magill-Solc C, Hartmann C, Helfrich B, Gilman L, Folkvord J, Helm K, Miller YE (February 1996). “Neutral endopeptidase: variable expression in human lung, inactivation in lung cancer, and modulation of peptide-induced calcium flux”. Cancer Res. 56 (4): 831-839. PMID 8631021.

- ^ Alasbahi R, Melzig MF (January 2008). “Screening of some Yemeni medicinal plants for inhibitory activity against peptidases”. Pharmazie 63 (1): 86-88. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1047849. PMID 18271311.

- ^ a b McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR (Sep 2014). “Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure”. The New England Journal of Medicine 371 (11): 993–1004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. hdl:10993/27659. PMID 25176015.

- ^ Venugopal J (2003). “Pharmacological modulation of the natriuretic peptide system”. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 13 (9): 1389–1409. doi:10.1517/13543776.13.9.1389.

- ^ McGowan P, Nelles N, Wimmer J, Williams D, Wen J, Li M, Ewton A, Curry C, Zu Y, Sheehan A, Chang CC (2012). “Differentiating between Burkitt lymphoma and CD10+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the role of commonly used flow cytometry cell markers and the application of a multiparameter scoring system”. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 137 (4): 665-670. doi:10.1309/AJCP3FEPX5BEEKGX. PMC 4975158. PMID 22431545.

- ^ Berglund M, Thunberg U, Amini RM, Book M, Roos G, Erlanson M, Linderoth J, Dictor M, Jerkeman M, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Sundström C, Rehn-Eriksson S, Backlin C, Hagberg H, Rosenquist R, Enblad G (2005). “Evaluation of immunophenotype in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its impact on prognosis”. Mod. Pathol. 18 (8): 1113-1120. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800396. PMID 15920553.

- ^ Höller S, Horn H, Lohr A, Mäder U, Katzenberger T, Kalla J, Bernd HW, Went P, Ott MM, Müller-Hermelink HK, Rosenwald A, Ott G (2009). “A cytomorphological and immunohistochemical profile of aggressive B-cell lymphoma: high clinical impact of a cumulative immunohistochemical outcome predictor score”. J Hematopathol 2 (4): 187-194. doi:10.1007/s12308-009-0044-x. PMC 2798934. PMID 20309427.

- ^ Xu Y, McKenna RW, Molberg KH, Kroft SH (2001). “Clinicopathologic analysis of CD10+ and CD10- diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Identification of a high-risk subset with coexpression of CD10 and bcl-2”. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 116 (2): 183-190. doi:10.1309/J7RN-UXAY-55GX-BUNK. PMID 11488064.

- ^ Fabiani B, Delmer A, Lepage E, Guettier C, Petrella T, Brière J, Penny AM, Copin MC, Diebold J, Reyes F, Gaulard P, Molina TJ (2004). “CD10 expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas does not influence survival”. Virchows Arch. 445 (6): 545-551. doi:10.1007/s00428-004-1129-7. PMID 15517363.

- ^ Baseggio L, Traverse-Glehen A, Berger F, Ffrench M, Jallades L, Morel D, Goedert G, Magaud JP, Salles G, Felman P (2011). “CD10 and ICOS expression by multiparametric flow cytometry in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma”. Mod. Pathol. 24 (7): 993–1003. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2011.53. PMID 21499231.

- ^ Yuan CM, Vergilio JA, Zhao XF, Smith TK, Harris NL, Bagg A (2005). “CD10 and BCL6 expression in the diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: utility of detecting CD10+ T cells by flow cytometry”. Hum. Pathol. 36 (7): 784-791. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2005.05.008. PMID 16084948.

- ^ Attygalle AD, Diss TC, Munson P, Isaacson PG, Du MQ, Dogan A (2004). “CD10 expression in extranodal dissemination of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma”. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 28 (1): 54–61. doi:10.1097/00000478-200401000-00005. PMID 14707864.

- ^ Cook JR, Craig FE, Swerdlow SH (2003). “Benign CD10-positive T cells in reactive lymphoid proliferations and B-cell lymphomas”. Mod. Pathol. 16 (9): 879-885. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000084630.64243.D1. PMID 13679451.

- ^ Yasir S, Herrera L, Gomez-Fernandez C, Reis IM, Umar S, Leveillee R, Kava B, Jorda M (2012). “CD10+ and CK7/RON- immunophenotype distinguishes renal cell carcinoma, conventional type with eosinophilic morphology from its mimickers”. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 20 (5): 454-461. doi:10.1097/PAI.0b013e31823fecd3. PMID 22417859.

- ^ a b Notohara K, Hamazaki S, Tsukayama C, Nakamoto S, Kawabata K, Mizobuchi K, Sakamoto K, Okada S (2000). “Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: immunohistochemical localization of neuroendocrine markers and CD10”. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 24 (10): 1361-1371. doi:10.1097/00000478-200010000-00005. PMID 11023097.

- ^ Córdoba A, Guerrero D, Larrinaga B, Iglesias ME, Arrechea MA, Yanguas JI (2009). “Bcl-2 and CD10 expression in the differential diagnosis of trichoblastoma, basal cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma with follicular differentiation”. Int. J. Dermatol. 48 (7): 713-717. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04076.x. PMID 19570076.

- ^ Sari Aslani F, Akbarzadeh-Jahromi M, Jowkar F (2013). “Value of CD10 Expression in Differentiating Cutaneous Basal from Squamous Cell Carcinomas and Basal Cell Carcinoma from Trichoepithelioma”. Iran J Med Sci 38 (2): 100-106. PMC 3700055. PMID 23825889.

- ^ Murali R, Delprado W (2005). “CD10 immunohistochemical staining in urothelial neoplasms”. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 124 (3): 371-379. doi:10.1309/04BH-F6A8-0BQM-H7HT. PMID 16191505.

- ^ Bahadir B, Behzatoglu K, Bektas S, Bozkurt ER, Ozdamar SO (2009). “CD10 expression in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder”. Diagn Pathol 4 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-4-38. PMC 2780995. PMID 19917108.

- ^ a b Mikami Y, Hata S, Kiyokawa T, Manabe T (2002). “Expression of CD10 in malignant müllerian mixed tumors and adenosarcomas: an immunohistochemical study”. Mod. Pathol. 15 (9): 923-930. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000026058.33869.DB. PMID 12218209.

- ^ McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, Maxwell P (2001). “CD10 is a sensitive and diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker of normal endometrial stroma and of endometrial stromal neoplasms”. Histopathology 39 (3): 273-278. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01215.x. PMID 11532038.

- ^ Kabbinavar FF, Hambleton J, Mass RD, Hurwitz HI, Bergsland E, Sarkar S (2005). “Combined analysis of efficacy: the addition of bevacizumab to fluorouracil/leucovorin improves survival for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer”. J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (16): 3706-3712. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.00.232. PMID 15867200.

- ^ Weinreb I, Cunningham KS, Perez-Ordoñez B, Hwang DM (2009). “CD10 is expressed in most epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas: a potential diagnostic pitfall”. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 133 (12): 1965-1968. doi:10.1043/1543-2165-133.12.1965. PMID 19961253.

- ^ Jung SM, Kuo TT (2005). “Immunoreactivity of CD10 and inhibin alpha in differentiating hemangioblastoma of central nervous system from metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma”. Mod. Pathol. 18 (6): 788-794. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800351. PMID 15578072.

- ^ Yin WH, Li J, Chan JK (2012). “Sporadic haemangioblastoma of the kidney with rhabdoid features and focal CD10 expression: report of a case and literature review”. Diagn Pathol 7 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-7-39. PMC 3364142. PMID 22497861.

外部リンク

[編集]- ペプチダーゼとその阻害因子に関するMEROPSオンラインデータベース: M13.001

- Neprilysin - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス