アデノ随伴ウイルス

この項目「アデノ随伴ウイルス」は途中まで翻訳されたものです。(原文:en:Adeno-associated virus 10 November 2009 at 10:42 UTC) 翻訳作業に協力して下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴、翻訳のガイドラインも参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2009年11月) |

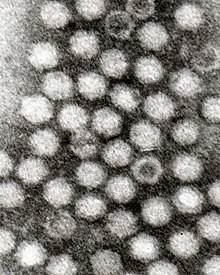

アデノ随伴ウイルス(英: Adeno-associated virus:AAV)とはヒトや霊長目の動物に感染する小型(20nm程度)の、パルボウイルス科ディペンドウイルス属に分類されるヘルパー依存型のエンベロープを持たないウイルスである。非常に弱い免疫反応しか引き起こさず、病原性は現在の所確認されていない。分裂期にある細胞にもそうでない細胞にもゲノムを送り込むことができ、宿主細胞にゲノムを送り込まずとも染色体外で生存することができる [1]。そのような特色があるためにベクターウイルスを用いた遺伝子治療やヒトの疾患モデル細胞の作成などに用いられる[2]。1型から5型まである。

遺伝子治療ベクター

[編集]利点と欠点

[編集]野生型のAAVは、病原性の欠落を主とする様々な特徴のために、遺伝子治療の研究者から多くの興味を集めてきた。このウイルスは、分裂していない細胞へと感染し、宿主細胞の19番染色体上のAAVS1と呼ばれる領域に挿入される。[3][4] この特徴は、ランダムな遺伝子挿入とそれによる突然変異や細胞の癌化を引き起こすレトロウイルスに比べて優れたものである。AAVの遺伝子の挿入はAAAVS1において発生するものがほとんどであり、ランダムな挿入は無視できる割合でしか発生しない。しかし、ウイルスベクターとしてのAAVの研究が進むにつれて、rep遺伝子とcap遺伝子を取り除くことで、この遺伝子の挿入能力も取り除かれている。 遺伝子治療のために作られた遺伝子配列は、プライマーの働きをする末端逆位配列(ITR)の間に挿入される。ウイルスによって作られた一本鎖DNAは、宿主細胞のDNAポリメラーゼによって二本鎖DNA になり、コンカテマーを形成する。分裂していない細胞においては、コンカテマーはそのままの状態で保存される。一方で分裂する細胞においては、エピソームDNAは宿主細胞によって複製されてないのでAAVのDNAは失われる。また、AAVは免疫原性をほとんど持っていないために抗体があまり産生されない。そのために、抗体依存性細胞傷害が明確には見られない[5][6][7]。 一方でこのウイルスベクターを用いることによるデメリットも存在する。AAVに搭載できる遺伝子配列は比較的限られており、多くの場合この遺伝子の4.8 kbpの配列を完全に置き換える必要がある。したがって大きな遺伝子はAAVベクターの使用には適していない。また、ウイルスの感染による液性免疫系の活性が発生することもデメリットとなる。免疫系によりAAVが無力化されるため、いくらかの用途ではAAVのメリットが制約される。そのため、多くの臨床実験では、免疫系の活性が弱い脳で行われている。 以上のように、AAVは、ウイルスベクターとして優れた特徴を持つために変種もつくられている。例えば自己相補型AAV(scAAV)は、二本鎖DNAを最初から形成するAAVの変種であり、通常のAAVと違い二本鎖DNAを形成する時間がかからないために効率に優れている。しかしながら、scAAVは二本鎖DNAを形成するため二本分の遺伝子配列を搭載するために通常のAAVにくらべて搭載できる遺伝子の大きさが半減する[8]。またscAAVは通常のAAVより高い免疫原性を保有しており細胞傷害性T細胞をより強く活性化させてしまう[9]。

臨床試験

[編集]現在までに、AAVは162の臨床試験に用いられている(遺伝子治療全体の6.9%)。[10] レーバー先天性黒内障[11][12][13]、血友病[14]、鬱血性心不全[15]、パーキンソン病[16]などの疾患においてPhase1あるいはPhase2での臨床試験における有望な結果が報告されている。

| 症候 | 遺伝子 | 投与法 | フェイズ | 被験者数 | 進行状況 |

| 嚢胞性線維症 | CFTR | エアロゾル吸入 | I | 12 | 完了 |

| CFTR | エアロゾル吸入 | II | 38 | 完了 | |

| CFTR | エアロゾル吸入 | II | 100 | 完了 | |

| 血友病 B | FIX | 筋肉内投与 | I | 9 | 完了 |

| FIX | 肝動脈内投与 | I | 6 | 終了 | |

| 関節炎 | TNFR:Fc | Intraarticular | I | 1 | 進行中 |

| 遺伝性肺気腫 | AAT | 筋肉内投与 | I | 12 | 進行中 |

| レーバー先天性黒内障 | 網膜下l | I-II | Multiple | Several 進行中 and 完了 | |

| 加齢黄斑変性 | sFlt-1 | 網膜下l | I-II | 24 | 進行中 |

| 筋ジストロフィー | Sarcoglycan | 筋肉内投与 | I | 10 | 進行中 |

| パーキンソン病 | GAD65, GAD67 | 頭蓋内 | I | 12 | 完了[18] |

| カナバン病 | AAC | 頭蓋内 | I | 21 | 進行中 |

| バッテン病 | CLN2 | 頭蓋内 | I | 10 | 進行中 |

| アルツハイマー病 | NGF | 頭蓋内 | I | 6 | 進行中 |

| 鬱血性心不全 | SERCA2a | Intra-coronary | IIb | 250 | 進行中 |

前立腺がんに対する臨床試験はphase IIIに達している[17] が、ex vivoでの研究はAAVの利用には含めていない。

病理学

[編集]AAVはいかなる疾患も引き起こさないと考えられている。しかし、AAVのDNAが変異した精子を含む精液においてよくみられることから、男性不妊症との関与が示唆されている。しかしAAVの感染と男性不妊症との因果関係は今のところ見つかっていない[19]。2015年、ヒト肝細胞癌の特定の遺伝子にAAV-2が挿入されていることが明らかになり、肝細胞癌への関与が強く示唆されている[20]。

ウイルスの構造

[編集]ゲノムの構造

[編集]AAVのゲノムは、4.7 kbpの一本鎖DNS(ssDNA)から成る。DNA鎖の末端には末端逆位配列(ITR)をもち、rep遺伝子とcap遺伝子の2つのオープンリーディングフレーム(ORF)を持つ。rep遺伝子は、AAVの生存に必要なRepタンパクをコードしており、cap遺伝子は、VP1,VP2,VP3という3つのカプシドタンパクをコードしている。cap遺伝子がコードするカプシドタンパクにより正二十面体のカプシドを形成する。[21]

ITR配列

[編集]ITRは両末端に存在する145 bpの配列である。ITRはAAVの増殖に必要とされる。[22] ITRはヘアピン構造をとり、この領域が複製開始点となるために、DNAプライメラーゼ無しでDNA合成を行なう事ができる(セルフプライミング)。また、ITRは野生型AAVにおける宿主細胞への遺伝子挿入や、[23][24] DNAase耐性を持ったカプシドの形成にも関与している[25]。

遺伝子治療に用いる範囲では、ITR配列唯一のシスエレメントであり、capとrepがトランスエレメントであるように見える。しかし、ITRはウイルスの複製及びカプシド形成の過程での唯一のシスエレメントでない可能性が示唆されている。一部の研究においては、rep遺伝子の配列の中にRep依存型シスエレメント(CARE)が存在することが示されておりCAREはシスエレメントとして増殖とカプシド形成を調整するとされる。 [26][27][28][29]

rep配列

[編集]ゲノムの左末端にはp5及びp19プロモーターと、イントロンを含むmRNA領域が存在する。したがってスプライシングの結果分子量の異なるRep78,Rep68,Rep52,Rep40の4つの転写産物が合成される。 [30] Rep78とRep68はITRのヘアピン構造に結合する。またRepタンパクはすべてATPと結びついてヘリカーゼ活性を発揮する。またp40プロモーターによって転写がアップレギュレーションされ、p5,p19プロモーターによって転写がダウンレギュレーションされる [24][30][31][32][33][34]

cap配列

[編集]The right side of a positive-sensed AAV genome encodes overlapping sequences of three capsid proteins, VP1, VP2 and VP3, which start from one promoter, designated p40. The molecular weights of these proteins are 87, 72 and 62 kiloDaltons, respectively.[35] All three of them are translated from one mRNA. After this mRNA is synthesized, it can be spliced in two different manners: either a longer or shorter intron can be excised resulting in the formation of two pools of mRNAs: a 2.3 kb- and a 2.6 kb-long mRNA pool. Usually, especially in the presence of adenovirus, the longer intron is preferred, so the 2.3-kb-long mRNA represents the so-called "major splice". In this form the first AUG codon, from which the synthesis of VP1 protein starts, is cut out, resulting in a reduced overall level of VP1 protein synthesis. The first AUG codon, which remains in the major splice, is the initiation codon for VP3 protein. However, upstream of that codon in the same open reading frame lies an ACG sequence (encoding threonine) which is surrounded by an optimal Kozak context. This contributes to a low level of synthesis of VP2 protein, which is actually VP3 protein with additional N terminal residues, as is VP1.[36][37][38][39]

Since the bigger intron is preferred to be spliced out, and since in the major splice the ACG codon is a much weaker translation initiation signal, the ratio at which the AAV structural proteins are synthesized in vivo is about 1:1:20, which is the same as in the mature virus particle.[40] The unique fragment at the N terminus of VP1 protein was shown to possess the phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity, which is probably required for the releasing of AAV particles from late endosomes.[41] Muralidhar et al. reported that VP2 and VP3 are crucial for correct virion assembly.[38] More recently, however, Warrington et al. showed VP2 to be unnecessary for the complete virus particle formation and an efficient infectivity, and also presented that VP2 can tolerate large insertions in its N terminus, while VP1 can not, probably because of the PLA2 domain presence.[42]

The crystal structure of the VP3 protein was determined by Xie, Bue, et al..[43]

AAVの血清型

[編集]2006年時点で、11種類のAAVの血清型が報告されており、11番目は2004年に報告された[44]。 既知の血清型のすべてが様々な種類の組織細胞に感染することができる。 組織特異性は、カプシドの血清型によって決定され、AAVベクターのシュードタイピング(pseudotyping)による指向性(tropism)の範囲は、治療上重要となる可能性がある。

AAV2

[編集]Serotype 2 (AAV2) has been the most extensively examined so far.[45][46][47][48][49][50] AAV2 presents natural tropism towards e.g. skeletal muscles,[51] neurons,[45] vascular smooth muscle cells[52] and hepatocytes.[53]

Three cell receptors have been described for AAV2: heparan sulfate proteoglican (HSPG), aVβ5 integrin and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR-1). The first functions as a primary receptor, while the latter two have a co-receptor activity and enable AAV to enter the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis.[54][55][56]) These study results have been disputed by Qiu, Handa, et al..[57] HSPG functions as the primary receptor, though its abundance in the extracellular matrix can scavenge AAV particles and impair the infection efficiency.[58]

AAV2とガン

[編集]試験により、血清型が2型のウイルス(AAV-2)は健常細胞を障害することなく、明らかにがん細胞を破壊する。

Studies have shown that serotype 2 of the virus (AAV-2) apparently kills cancer cells without harming healthy ones. "Our results suggest that adeno-associated virus type 2, which infects the majority of the population but has no known ill effects, kills multiple types of cancer cells yet has no effect on healthy cells," said Craig Meyers,[59] a professor of immunology and microbiology at the Penn State College of Medicine in Pennsylvania.[60] This could lead to a new anti-cancer agent.

他の血清型

[編集]Although AAV2 is the most popular serotype in various AAV-based research, it has been shown that other serotypes can be more effective as gene delivery vectors. For instance AAV6 appears much better in infecting airway epithelial cells, AAV7 presents very high transduction rate of murine skeletal muscle cells (similarly to AAV1 and AAV5), AAV8 is superb in transducing hepatocytes[61][62][63] and AAV1 and 5 were shown to be very efficient in gene delivery to vascular endothelial cells.[64] AAV6, a hybrid of AAV1 and AAV2,[63] also shows lower immunogenicity than AAV2.[62]

Serotypes can differ with the respect to the receptors they are bound to. For example AAV4 and AAV5 transduction can be inhibited by soluble sialic acids (of different form for each of these serotypes),[65] and AAV5 was shown to enter cells via the platelet-derived growth factor receptor.[66]

免疫学

[編集]ヒトにおいて、AAVによって惹起される免疫応答は明らかに限定的であることから、AAVは特に遺伝子治療専門家の興味の対象である。この要因は、免疫関連症状の発生リスクを低減する一方で、ベクターの形質導入の効率性に肯定的に影響するであろう。

自然免疫

[編集]AAVベクターに対する自然免疫反応はの特徴は、動物モデルで明らかにされている。

The innate immune response to the AAV vectors has been characterised in animal models. Intravenous administration in mice causes transient production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and some infiltration of neutrophils and other leukocytes into the liver, which seems to sequester a large percentage of the injected viral particles. Both soluble factor levels and cell infiltration appear to return to baseline within six hours. By contrast, more aggressive viruses produce innate responses lasting 24 hours or longer.[67]

液性免疫

[編集]The virus is known to instigate robust humoral immunity in animal models and in the human population where up to 80% of individuals are thought to be seropositive for AAV2. Antibodies are known to be neutralising and for gene therapy applications these do impact on vector transduction efficiency via some routes of administration. As well as persistent AAV specific antibody levels, it appears from both prime-boost studies in animals and from clinical trials that the B-cell memory is also strong.[68] In seropositive humans, circulating IgG antibodies for AAV2 appear to be primarily composed of the IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses, with little or no IgG3 or IgG4 present.[69]

細胞免疫

[編集]The cell-mediated response to the virus and to vectors is poorly characterised and has been largely ignored in the literature as recently as 2005.[68] Clinical trials using an AAV2-based vector to treat haemophilia B seem to indicate that targeted destruction of transduced cells may be occurring.[70] Combined with data that shows that CD8+ T-cells can recognise elements of the AAV capsid in vitro[71], it appears that there may be a cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to AAV vectors. Cytotoxic responses would imply the involvement of CD4+ T helper cells in the response to AAV and in vitro data from human studies suggests that the virus may indeed induce such responses including both Th1 and Th2 memory responses.[69] A number of candidate T cell stimulating epitopes have been identified within the AAV capsid protein VP1, which may be attractive targets for modification of the capsid if the virus is to be used as a vector for gene therapy.[69][70]

AAVの感染サイクル

[編集]AAVの感染サイクルにはいくつかの段階があり、細胞感染から感染性粒子の産生まである

- 細胞膜への付着

- エンドサイトーシス(形質膜陥入)

- エンドソームによる輸送

- 後期エンドソーム(エンドサイトーシスで形成されるリソソームへの運搬小胞)後期又はリソソームからの脱出(escape)

- 核へのトランスロケーション(転位)

- AAVゲノムの複製型である二本鎖DNAの形成

- rep 遺伝子の発現

- ゲノムの複製

- cap 遺伝子の発現、子孫(後代)一本鎖DNA粒子の合成

- 完全なウイルス粒子の組立て、及び

- 感染細胞からの放出

これらの段階の一部は、様々な細胞の種類で異なることがあり、明確でかなり限定的なAAVのネイティブトロピズム(native tropism)に寄与する。ウイルスの複製は、細胞がどの細胞周期にあるかによって、1種類の細胞でも異なる可能性がある。[71]

Some of these steps may look different in various types of cells, which, in part, contributes to the defined and quite limited native tropism of AAV. Replication of the virus can also vary in one cell type, depending on the cell's current cell cycle phase.[71] The characteristic feature of the adeno-associated virus is a deficiency in replication and thus its inability to multiply in unaffected cells. The first factor that was described as providing successful generation of new AAV particles, was the adenovirus, from which the AAV name originated. It was then shown that AAV replication can be facilitated by selected proteins derived from the adenovirus genome,[72][73] by other viruses such as HSV,[74] or by genotoxic agents, such as UV irradiation or hydroxyurea.[75][76][77]

The minimal set of the adenoviral genes required for efficient generation of progeny AAV particles, was discovered by Matsushita, Ellinger et al..[72] This discovery allowed for new production methods of recombinant AAV, which do not require adenoviral co-infection of the AAV-producing cells. In the absence of helper virus or genotoxic factors, AAV DNA can either integrate into the host genome or persist in episomal form. In the former case integration is mediated by Rep78 and Rep68 proteins and requires the presence of ITRs flanking the region being integrated. In mice, the AAV genome has been observed persisting for long periods of time in quiescent tissues, such as skeletal muscles, in episomal form (a circular head-to-tail conformation).[78]

引用文献

[編集]- ^ Russel DW, Deyle DR (2010). “Adeno- associated virus vector integration”. Current Opinion in Molecular Therapy 11 (4): 442-447. PMC 2929125. PMID 19649989.

- ^ Grieger JC, Samulski RJ (2005). “Adeno-associated virus as a gene therapy vector: vector development, production and clinical applications”. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/biotechnology. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology 99: 119?45. doi:10.1007/10_005. ISBN 3-540-28404-4. PMID 16568890.

- ^ Kotin RM, Siniscalco M, Samulski RJ, et al. (1 March 1990). “Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87 (6): 2211–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. PMC 53656. PMID 2156265.

- ^ Surosky RT, Urabe M, Godwin SG, et al. (1 October 1997). “Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins target DNA sequences to a unique locus in the human genome”. Journal of Virology 71 (10): 7951–9. PMC 192153. PMID 9311886.

- ^ Chirmule N, Propert K, Magosin S, Qian Y, Qian R, Wilson J (September 1999). “Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans”. Gene Therapy 6 (9): 1574–83. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3300994. PMID 10490767.

- ^ Hernandez YJ, Wang J, Kearns WG, Loiler S, Poirier A, Flotte TR (1 October 1999). “Latent Adeno-Associated Virus Infection Elicits Humoral but Not Cell-Mediated Immune Responses in a Nonhuman Primate Model”. Journal of Virology 73 (10): 8549–58. PMC 112875. PMID 10482608.

- ^ Ponnazhagan S, Mukherjee P, Yoder MC, et al. (April 1997). “Adeno-associated virus 2-mediated gene transfer in vivo: organ-tropism and expression of transduced sequences in mice”. Gene 190 (1): 203–10. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00576-8. PMID 9185868.

- ^ McCarty, D M; Monahan, P E; Samulski, R J (2001). “Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis”. Gene Therapy 8 (16): 1248–54. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3301514. PMID 11509958.

- ^ Rogers GL (Jan 2014). “Role of the vector genome and underlying factor IX mutation in immune responses to AAV gene therapy for hemophilia B..”. J Transl Med. 12. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-12-25. PMC 3904690. PMID 24460861.

- ^ J. of Gene Medicine, http://www.abedia.com/wiley/vectors.php

- ^ Maguire, A. M., Simonelli, F., Pierce, E. A., Pugh, E. N., Mingozzi, F., Bennicelli, J., Banfi, S., et al. (2008). Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis The New England journal of medicine, 358(21), 2240–2248. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802315

- ^ Bainbridge, J. W. B., Smith, A. J., Barker, S. S., Robbie, S., Henderson, R., Balaggan, K., Viswanathan, A., et al. (2008). Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis The New England journal of medicine, 358(21), 2231–2239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802268 PMID 18441371

- ^ Hauswirth, W. W., Aleman, T. S., Kaushal, S., Cideciyan, A. V., Schwartz, S. B., Wang, L., Conlon, T. J., et al. (2008). Treatment of Leber Congenital Amaurosis Due to RPE65Mutations by Ocular Subretinal Injection of Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Vector: Short-Term Results of a Phase I Trial. Human gene therapy, 19(10), 979–990. doi:10.1089/hum.2008.107 PMID 18774912

- ^ Nathwani, A. C., Tuddenham, E. G. D., Rangarajan, S., Rosales, C., McIntosh, J., Linch, D. C., Chowdary, P., et al. (2011). Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B The New England journal of medicine, 365(25), 2357–2365. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1108046

- ^ Jessup, M; Greenberg B, Mancini DM, Cappola T, Pauly DF, Jaski B, Yaroshinsky A, Zsebo K, Dittrich H, Hajjar, RJ (June 2011). “Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure”. Circulation 124 (3): 304–313. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022889. ISSN 1524-4539. PMID 21709064 2012年3月24日閲覧。.

- ^ LeWitt, P. A., Rezai, A. R., Leehey, M. A., Ojemann, S. G., Flaherty, A. W., Eskandar, E. N., Kostyk, S. K., et al. (2011). AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial. The Lancet Neurology, 10(4), 309–319. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70039-4 PMID 21419704

- ^ a b Carter BJ (May 2005). “Adeno-associated virus vectors in clinical trials”. Human Gene Therapy 16 (5): 541?50. doi:10.1089/hum.2005.16.541. PMID 15916479.

- ^ Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, et al. (June 2007). “Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson's disease: an open label, phase I trial”. Lancet 369 (9579): 2097?105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. PMID 17586305.

- ^ Erles K, Rohde V, Thaele M, Roth S, Edler L, Schlehofer JR (November 2001). “DNA of adeno-associated virus (AAV) in testicular tissue and in abnormal semen samples”. Human Reproduction 16 (11): 2333–7. doi:10.1093/humrep/16.11.2333. PMID 11679515.

- ^ Nault JC, Datta S, Imbeaud S, Franconi A, Mallet M, Couchy G, Letouzé E, Pilati C, Verret B, Blanc JF, Balabaud C, Calderaro J, Laurent A, Letexier M, Bioulac-Sage P, Calvo F, Zucman-Rossi J. "Recurrent AAV2-related insertional mutagenesis in human hepatocellular carcinomas" Nat Genet. 2015 Oct;47(10):1187-93. doi:10.1038/ng.3389. Epub 2015 Aug 24. PMID 26301494

- ^ Carter, BJ (2000). “Adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors for gene delivery”. In DD Lassic & N Smyth Templeton. Gene Therapy: Therapeutic Mechanisms and Strategies. New York City: Marcel Dekker, Inc.. pp. 41–59. ISBN 0-585-39515-2

- ^ Bohenzky RA, LeFebvre RB, Berns KI (October 1988). “Sequence and symmetry requirements within the internal palindromic sequences of the adeno-associated virus terminal repeat”. Virology 166 (2): 316–27. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(88)90502-8. PMID 2845646.

- ^ Wang XS, Ponnazhagan S, Srivastava A (July 1995). “Rescue and replication signals of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome”. Journal of Molecular Biology 250 (5): 573–80. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1995.0398. PMID 7623375.

- ^ a b Weitzman MD, Kyöstiö SR, Kotin RM, Owens RA (June 1994). “Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91 (13): 5808–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. PMC 44086. PMID 8016070.

- ^ Zhou X, Muzyczka N (April 1, 1998). “In vitro packaging of adeno-associated virus DNA”. Journal of Virology 72 (4): 3241–7. PMC 109794. PMID 9525651.

- ^ Nony P, Tessier J, Chadeuf G, et al. (October 2001). “Novel cis-acting replication element in the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome is involved in amplification of integrated rep-cap sequences”. Journal of Virology 75 (20): 9991–4. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.20.9991-9994.2001. PMC 114572. PMID 11559833.

- ^ Nony P, Chadeuf G, Tessier J, Moullier P, Salvetti A (January 2003). “Evidence for packaging of rep-cap sequences into adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 capsids in the absence of inverted terminal repeats: a model for generation of rep-positive AAV particles”. Journal of Virology 77 (1): 776–81. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.1.776-781.2003. PMC 140600. PMID 12477885.

- ^ Philpott NJ, Giraud-Wali C, Dupuis C, et al. (June 2002). “Efficient integration of recombinant adeno-associated virus DNA vectors requires a p5-rep sequence in cis”. Journal of Virology 76 (11): 5411–21. doi:10.1128/JVI.76.11.5411-5421.2002. PMC 137060. PMID 11991970.

- ^ Tullis GE, Shenk T (December 2000). “Efficient replication of adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors: a cis-acting element outside of the terminal repeats and a minimal size”. Journal of Virology 74 (24): 11511–21. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.24.11511-11521.2000. PMC 112431. PMID 11090148.

- ^ a b Kyöstiö SR, Owens RA, Weitzman MD, Antoni BA, Chejanovsky N, Carter BJ (May 1, 1994). “Analysis of adeno-associated virus (AAV) wild-type and mutant Rep proteins for their abilities to negatively regulate AAV p5 and p19 mRNA levels”. Journal of Virology 68 (5): 2947–57. PMC 236783. PMID 8151765.

- ^ Im DS, Muzyczka N (May 1990). “The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity”. Cell 61 (3): 447–57. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-K. PMID 2159383.

- ^ Im DS, Muzyczka N (February 1, 1992). “Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization”. Journal of Virology 66 (2): 1119–28. PMC 240816. PMID 1309894.

- ^ Samulski RJ (2003). “AAV vectors, the future workhorse of human gene therapy”. Ernst Schering Research Foundation Workshop (43): 25–40. PMID 12894449.

- ^ Trempe JP, Carter BJ (January 1, 1988). “Regulation of adeno-associated virus gene expression in 293 cells: control of mRNA abundance and translation”. Journal of Virology 62 (1): 68–74. PMC 250502. PMID 2824856.

- ^ Jay FT, Laughlin CA, Carter BJ (May 1981). “Eukaryotic translational control: adeno-associated virus protein synthesis is affected by a mutation in the adenovirus DNA-binding protein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 78 (5): 2927–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.5.2927. PMC 319472. PMID 6265925.

- ^ Becerra SP, Rose JA, Hardy M, Baroudy BM, Anderson CW (December 1985). “Direct mapping of adeno-associated virus capsid proteins B and C: a possible ACG initiation codon”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 82 (23): 7919–23. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.23.7919. PMC 390881. PMID 2999784.

- ^ Cassinotti P, Weitz M, Tratschin JD (November 1988). “Organization of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsid gene: mapping of a minor spliced mRNA coding for virus capsid protein 1”. Virology 167 (1): 176–84. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(88)90067-0. PMID 2847413.

- ^ a b Muralidhar S, Becerra SP, Rose JA (January 1, 1994). “Site-directed mutagenesis of adeno-associated virus type 2 structural protein initiation codons: effects on regulation of synthesis and biological activity”. Journal of Virology 68 (1): 170–6. PMC 236275. PMID 8254726.

- ^ Trempe JP, Carter BJ (September 1, 1988). “Alternate mRNA splicing is required for synthesis of adeno-associated virus VP1 capsid protein”. Journal of Virology 62 (9): 3356–63. PMC 253458. PMID 2841488.

- ^ Rabinowitz JE, Samulski RJ (December 2000). “Building a better vector: the manipulation of AAV virions”. Virology 278 (2): 301–8. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0707. PMID 11118354.

- ^ Girod A, Wobus CE, Zádori Z, et al. (May 1, 2002). “The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity”. The Journal of General Virology 83 (Pt 5): 973–8. PMID 11961250.

- ^ Warrington KH, Gorbatyuk OS, Harrison JK, Opie SR, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N (June 2004). “Adeno-associated virus type 2 VP2 capsid protein is nonessential and can tolerate large peptide insertions at its N terminus”. Journal of Virology 78 (12): 6595–609. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.12.6595-6609.2004. PMC 416546. PMID 15163751.

- ^ Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, et al. (August 2002). “The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (16): 10405–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.162250899. PMC 124927. PMID 12136130.

- ^ Mori S, Wang L, Takeuchi T, Kanda T (December 2004). “Two novel adeno-associated viruses from cynomolgus monkey: pseudotyping characterization of capsid protein”. Virology 330 (2): 375–83. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.012. PMID 15567432.

- ^ a b Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ, McCown TJ (May 1998). “Selective and rapid uptake of adeno-associated virus type 2 in brain”. Human Gene Therapy 9 (8): 1181–6. doi:10.1089/hum.1998.9.8-1181. PMID 9625257.

- ^ Fischer AC, Beck SE, Smith CI, et al. (December 2003). “Successful transgene expression with serial doses of aerosolized rAAV2 vectors in rhesus macaques”. Molecular Therapy 8 (6): 918–26. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.015. PMID 14664794.

- ^ Nicklin SA, Buening H, Dishart KL, et al. (September 2001). “Efficient and selective AAV2-mediated gene transfer directed to human vascular endothelial cells”. Molecular Therapy 4 (3): 174–81. doi:10.1006/mthe.2001.0424. PMID 11545607.

- ^ Rabinowitz JE, Xiao W, Samulski RJ (December 1999). “Insertional mutagenesis of AAV2 capsid and the production of recombinant virus”. Virology 265 (2): 274–85. doi:10.1006/viro.1999.0045. PMID 10600599.

- ^ Shi W, Bartlett JS (April 2003). “RGD inclusion in VP3 provides adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2)-based vectors with a heparan sulfate-independent cell entry mechanism”. Molecular Therapy 7 (4): 515–25. doi:10.1016/S1525-0016(03)00042-X. PMID 12727115.

- ^ Wu P, Xiao W, Conlon T, et al. (September 2000). “Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid gene and construction of AAV2 vectors with altered tropism”. Journal of Virology 74 (18): 8635–47. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.18.8635-8647.2000. PMC 102071. PMID 10954565.

- ^ Manno CS, Chew AJ, Hutchison S, et al. (April 2003). “AAV-mediated factor IX gene transfer to skeletal muscle in patients with severe hemophilia B”. Blood 101 (8): 2963–72. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-10-3296. PMID 12515715.

- ^ Richter M, Iwata A, Nyhuis J, et al. (April 2000). “Adeno-associated virus vector transduction of vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo”. Physiological Genomics 2 (3): 117–27. PMID 11015590.

- ^ Koeberl DD, Alexander IE, Halbert CL, Russell DW, Miller AD (February 1997). “Persistent expression of human clotting factor IX from mouse liver after intravenous injection of adeno-associated virus vectors”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94 (4): 1426–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.4.1426. PMC 19807. PMID 9037069.

- ^ Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, Zhou S, Dwarki V, Srivastava A (January 1999). “Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2”. Nature Medicine 5 (1): 71–7. doi:10.1038/4758. PMID 9883842.

- ^ Summerford C, Samulski RJ (February 1, 1998). “Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions”. Journal of Virology 72 (2): 1438–45. PMC 124624. PMID 9445046.

- ^ Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ (January 1999). “AlphaVbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection”. Nature Medicine 5 (1): 78–82. doi:10.1038/4768. PMID 9883843.

- ^ Qiu J, Handa A, Kirby M, Brown KE (March 2000). “The interaction of heparin sulfate and adeno-associated virus 2”. Virology 269 (1): 137–47. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0205. PMID 10725206.

- ^ Pajusola K, Gruchala M, Joch H, Lüscher TF, Ylä-Herttuala S, Büeler H (November 2002). “Cell-type-specific characteristics modulate the transduction efficiency of adeno-associated virus type 2 and restrain infection of endothelial cells”. Journal of Virology 76 (22): 11530–40. doi:10.1128/JVI.76.22.11530-11540.2002. PMC 136795. PMID 12388714.

- ^ “Common virus 'kills cancer'”. CNN. (6月22日2005年) 8月5日2009年閲覧。

- ^ http://www.fred.psu.edu/ds/retrieve/fred/investigator/cmm10

- ^ Gao GP, Alvira MR, Wang L, Calcedo R, Johnston J, Wilson JM (September 2002). “Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (18): 11854–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.182412299. PMC 129358. PMID 12192090.

- ^ a b Halbert CL, Allen JM, Miller AD (July 2001). “Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors”. Journal of Virology 75 (14): 6615–24. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.14.6615-6624.2001. PMC 114385. PMID 11413329.

- ^ a b Rabinowitz JE, Bowles DE, Faust SM, Ledford JG, Cunningham SE, Samulski RJ (May 2004). “Cross-dressing the virion: the transcapsidation of adeno-associated virus serotypes functionally defines subgroups”. Journal of Virology 78 (9): 4421–32. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.9.4421-4432.2004. PMC 387689. PMID 15078923.

- ^ Chen S, Kapturczak M, Loiler SA, et al. (February 2005). “Efficient transduction of vascular endothelial cells with recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 1 and 5 vectors”. Human Gene Therapy 16 (2): 235–47. doi:10.1089/hum.2005.16.235. PMC 1364465. PMID 15761263.

- ^ Kaludov N, Brown KE, Walters RW, Zabner J, Chiorini JA (August 2001). “Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity”. Journal of Virology 75 (15): 6884–93. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.15.6884-6893.2001. PMC 114416. PMID 11435568.

- ^ Di Pasquale G, Davidson BL, Stein CS, et al. (October 2003). “Identification of PDGFR as a receptor for AAV-5 transduction”. Nature Medicine 9 (10): 1306–12. doi:10.1038/nm929. PMID 14502277.

- ^ Zaiss AK, Liu Q, Bowen GP, Wong NC, Bartlett JS, Muruve DA (May 2002). “Differential activation of innate immune responses by adenovirus and adeno-associated virus vectors”. Journal of Virology 76 (9): 4580–90. doi:10.1128/JVI.76.9.4580-4590.2002. PMC 155101. PMID 11932423.

- ^ a b Zaiss AK, Muruve DA (June 2005). “Immune responses to adeno-associated virus vectors”. Current Gene Therapy 5 (3): 323–31. doi:10.2174/1566523054065039. PMID 15975009.

- ^ a b c Madsen, D.; Cantwell, E.R.; O'Brien, T.; Johnson, P.A.; Mahon, B.P. (2009), “Adeno-associated virus serotype 2 induces cell-mediated immune responses directed against multiple epitopes of the capsid protein VP1”, Journal of General Virology 90 (11): 2622–2633 2009年11月4日閲覧。

- ^ a b Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, et al. (March 2006). “Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response”. Nature Medicine 12 (3): 342–7. doi:10.1038/nm1358. PMID 16474400.

- ^ Sabatino DE, Mingozzi F, Hui DJ, et al. (December 2005). “Identification of mouse AAV capsid-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes”. Molecular Therapy 12 (6): 1023–33. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.009. PMID 16263332.

- ^ a b Matsushita T, Elliger S, Elliger C, et al. (July 1998). “Adeno-associated virus vectors can be efficiently produced without helper virus”. Gene Therapy 5 (7): 938–45. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3300680. PMID 9813665.

- ^ Myers MW, Laughlin CA, Jay FT, Carter BJ (July 1, 1980). “Adenovirus helper function for growth of adeno-associated virus: effect of temperature-sensitive mutations in adenovirus early gene region 2”. Journal of Virology 35 (1): 65–75. PMC 288783. PMID 6251278.

- ^ Handa H, Carter BJ (July 25, 1979). “Adeno-associated virus DNA replication complexes in herpes simplex virus or adenovirus-infected cells”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 254 (14): 6603–10. PMID 221504.

- ^ Yalkinoglu AO, Heilbronn R, Bürkle A, Schlehofer JR, zur Hausen H (June 1, 1988). “DNA amplification of adeno-associated virus as a response to cellular genotoxic stress”. Cancer Research 48 (11): 3123–9. PMID 2835153.

- ^ Yakobson B, Koch T, Winocour E (April 1, 1987). “Replication of adeno-associated virus in synchronized cells without the addition of a helper virus”. Journal of Virology 61 (4): 972–81. PMC 254052. PMID 3029431.

- ^ Yakobson B, Hrynko TA, Peak MJ, Winocour E (March 1, 1989). “Replication of adeno-associated virus in cells irradiated with UV light at 254 nm”. Journal of Virology 63 (3): 1023–30. PMC 247794. PMID 2536816.

- ^ Duan D, Sharma P, Yang J, et al. (November 1, 1998). “Circular intermediates of recombinant adeno-associated virus have defined structural characteristics responsible for long-term episomal persistence in muscle tissue”. Journal of Virology 72 (11): 8568–77. PMC 110267. PMID 9765395.