触肢

左上から順に、1段目:ウミグモ、カブトガニ(雄)、ザトウムシ、2段目:ダニ(胸板ダニ類)、ダニ(マダニ)、クツコムシ、3段目:ヒヨケムシ、カニムシ、サソリ、4段目:クモ(雄)、ウデムシ、サソリモドキ

触肢(しょくし、英語: pedipalp, palp)とは、クモ・サソリなどの鋏角類の節足動物に特有で、鋏角の直後にある第2対の付属肢(関節肢)である。種類により感覚や捕食などに用いられる[1]。古くは触鬚(しょくしゅ)とも呼ばれる。

概説

[編集]

触肢は鋏角類の前体(鋏角類の頭部に該当する合体節)に特有で、鋏角と口の直後から生えた1対の付属肢である。発生学上では後大脳に対応する第2体節由来で、分類群により様々な形態と機能をもつ[1]。例えばカブトガニなどでは直後の脚と同形で、歩脚の一部として用いられる。一方、クモガタ類では顕著に脚から区別され、歩行以外の機能を担うのが一般的である。例えばサソリでは捕食用の鋏、クモの雄では交接用の器官となっている[1]。また、口と鋏角に隣接した触肢の付け根、いわゆる基節 (coxa) が摂食を補助する内突起 (endite) をもつ場合が多い[2]。

節口類の触肢

[編集]カブトガニ類とウミサソリ類などが属する節口類(節口綱、腿口綱、Merostomata)の触肢は特化せず、脚との顕著な区別がつかない場合が一般的である。そのため、節口類の触肢は形態学的に脚扱いとされ、前体の付属肢構成が「鋏角1対・脚5対」として記載されることもある(通常およびクモガタ類の場合は「鋏角1対・触肢1対・脚4対」となる)[3]。内突起も原則として直後の脚と同様、顎基 (gnathobase) という鋸歯状の咀嚼器となっている[2]。

- カブトガニ類(剣尾類、Xiphosura)の触肢は少なくとも第1-4脚とほぼ同形である[1]。しかしカブトガニ科の場合は性的二形で、雄の触肢のみ、もしくは次の1対の脚と共に先端が鉤状に特化し、繁殖行動で雌を把握するのに用いられる[4][5]。

- ウミサソリ類(広翼類、Eurypterida)とカスマタスピス類(Chasmataspidida)の触肢は、肢節数(先端の爪をも含めて7節)以外では原則として脚(8-9節)と同形である。ただしウミサソリ類では触肢のみ(スリモニア、エレトプテルスなど)、もしく触肢と直後1対以上の脚(ミクソプテルス、メガログラプトゥスなど)が共に特化した種類や、カブトガニ類のように触肢が性的二形な種類もある(ユーリプテルスなど)[6][7]。

クモガタ類の触肢

[編集]-

クモの雄

クモガタ類(クモ形類、蛛形類、Arachnida)の触肢は多様で、分類群により単調な歩脚状からあらゆる形まで多岐にわたる。コヨリムシを除き、クモガタ類の触肢は形態(脚とは明らかに異なる)や見かけ上6節の肢節数(蹠節 metatarsus はなく、7節以上の脚より少ない)により明確に脚から区別され、感覚や捕食などという歩行以外の機能を担っている[1]。節口類とは異なり、多くのクモガタ類は触肢基節のみ内突起をもつ[2]。基節が往々にして口の左右を覆いかぶさり、直前にある鋏角・上唇 (labrum)・口上突起 (epistome) などと共に何らかの複合体を構成する場合もある[2][8]。

- クモの触肢は短い歩脚状で感覚や摂食を補助するのに用いられ、基節の内突起は口の左右を覆いかぶさった下顎 (maxilla) となる[9][2]。性的二形で、雄の場合では同時に交接用の器官でもあり、先端の腹面には精液を蓄える触肢器(palpal organ, 移精器官)という複雑な構造体をもつ[9][1]。

- サソリの触肢は捕獲器であり、先端2節が発達した鋏状である[1]。基節は口の左右を覆いかぶさり、鋏角・上唇・第1-2脚の顎葉(coxapophyses)と共に「stomotheca」という口器を構成する[10]。

- カニムシの触肢はサソリによく似た鋏状である。ただしカニムシの場合、触肢基節の内突起が口上突起と癒合して「rostrum」という嘴状の口器をなし[8]、鋏に毒腺をもつ[11]。

- ウデムシの触肢は鎌状の捕獲器であり、第3-4節が腕のように折りたたみ、内側に棘が生えている[1]。

- サソリモドキとヤイトムシの触肢も鎌状の捕獲器であるが、ウデムシほど極端ではない。サソリモドキの場合、触肢の先端2節が鋏となり、直前の第4節も発達した棘が1本ある[1]。

- ヒヨケムシの触肢は脚のように発達した歩脚状で、収納可能な吸盤 (suctural organ) を先端にもつ。基節はカニムシに似て、口上突起と癒合して嘴状の rostrum を構成する[8]。主に感覚と捕食に用いられ、平滑な表面を登る時も役に立つ[12]。

- ザトウムシの触肢は基本ではクモに似た歩脚状だが、捕獲器に特化した種類も少なくない。例えばアカザトウムシ亜目では内側に棘が生えて、しばしば強大な鎌状となる[13]。イトグチザトウムシ科では表面がモウセンゴケのように、小さな虫を粘りつく粘毛が生えている[14][13]。基節の内突起は直後の第1-2脚のものと共に顎葉となり、これはサソリに似て、鋏角・上唇などと共に stomotheca を構成する[15]。

- クツコムシの触肢は目立たなく、短い鎌のように前体の下に折りたたまれる。先端には小さな鋏と感覚器があり、感覚と物を掴む機能を兼ね備えたと考えられる[16]。

- ダニの触肢は基本として短い歩脚状であるが、基節が高度に癒合し、鋏角や口上突起などと共に顎体部 (gnathosoma) を構成する[17][8]。

- コヨリムシの触肢は短い歩脚状であるが、他のクモガタ類とは異なり、見かけ上9節で、脚のように歩行に用いられる[18]。

ウミグモ類の触肢

[編集]

-

長い触肢(最も内側1対の付属肢)をもつオオウミグモの1種

-

触肢をもたない Pycnogonum littorale

ウミグモ類(皆脚類、Pycnogonida)の触肢は明確に脚から区別され、鋏肢と担卵肢の間にある付属肢である[1]。単調な歩脚状で4-9節の肢節に分かれ[19]、感覚や摂食に用いられる[20]。なお、触肢が完全に退化消失したウミグモ類もある[20]。

英語などの場合、ウミグモ類の触肢は一般に「palp」と呼ばれ、他の鋏角類(真鋏角類)の触肢「pedipalp」から区別される[1][3]。

大顎類との対応関係

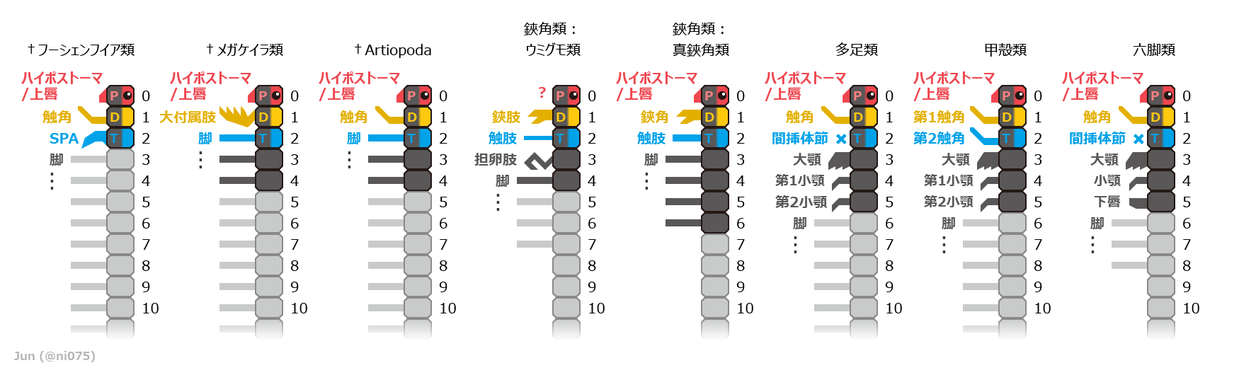

[編集]20世紀の主流な見解では、節足動物の中で鋏角類は第1体節(中大脳性)の触角を退化し、その鋏角は第2体節由来(後大脳性)と考えられたため、その直後にある触肢は第3体節由来で、大顎類(多足類・甲殻類・六脚類)の大顎に相同と解釈されてきた[21]。しかし90年代以降では、ホメオティック遺伝子発現[21][22][23][24][25]・発生学[26]・神経解剖学[26][27]など多方面な証拠により、鋏角類は常に第1体節をもち、鋏角と触肢はそれぞれ第1体節と第2体節由来(中大脳性と後大脳性)だと判明したことに連れて、鋏角は大顎類の第1触角に、触肢は甲殻類の第2触角(多足類と六脚類の場合は該当付属肢が退化)に相同だと見直されるようになった。

体節 分類群

|

先節

(前大脳) |

1

(中大脳) |

2

(後大脳) |

3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 大顎類 | 上唇 | 第1触角 | 第2触角/(退化) | 大顎 | 第1小顎 | 第2小顎/下唇 | 脚 |

| 鋏角類 | 上唇 | 鋏角 | 触肢 | 脚 | 脚 | 脚 | 脚 |

脚注

[編集]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lamsdell, James C.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2017). “Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 395–418. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b c d e Haug, Carolin (2020-08-13). “The evolution of feeding within Euchelicerata: data from the fossil groups Eurypterida and Trigonotarbida illustrate possible evolutionary pathways” (英語). PeerJ 8: e9696. doi:10.7717/peerj.9696. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ a b Alexeeva, Nina; Tamberg, Yuta; Shunatova, Natalia (2018-05-01). “Postembryonic development of pycnogonids: A deeper look inside” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 47 (3): 299–317. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2018.03.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Bicknell, Russell D. C.; Klinkhamer, Ada J.; Flavel, Richard J.; Wroe, Stephen; Paterson, John R. (2018-02-14). “A 3D anatomical atlas of appendage musculature in the chelicerate arthropod Limulus polyphemus” (英語). PLOS ONE 13 (2): e0191400. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191400. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5812571. PMID 29444161.

- ^ Bicknell, Russell D. C.; Brougham, Tom; Charbonnier, Sylvain; Sautereau, Frédéric; Hitij, Tomaž; Campione, Nicolás E. (2019-06-17). “On the appendicular anatomy of the xiphosurid Tachypleus syriacus and the evolution of fossil horseshoe crab appendages” (英語). The Science of Nature 106 (7): 38. doi:10.1007/s00114-019-1629-6. ISSN 1432-1904.

- ^ Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao P.; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (2015-09-01). “The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa”. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15 (1): 169. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 4556007. PMID 26324341.

- ^ Selden, Paul A. (1981). “Functional morphology of the prosoma of Baltoeurypterus tetragonophthalmus (Fischer) (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)” (英語). Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 72 (1): 9–48. doi:10.1017/S0263593300003217. ISSN 1473-7116.

- ^ a b c d Starck, J. Matthias; Belojević, Jelena; Brozio, Jason; Mehnert, Lisa (2022-03-01). “Comparative anatomy of the rostrosoma of Solifugae, Pseudoscorpiones and Acari” (英語). Zoomorphology 141 (1): 57–80. doi:10.1007/s00435-021-00551-3. ISSN 1432-234X.

- ^ a b Murillo, Wilder Ferney Zapata (2011) (英語). Biology of Spiders.

- ^ Howard, Richard J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Legg, David A.; Pisani, Davide; Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus (2019-03-01). “Exploring the evolution and terrestrialization of scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones) with rocks and clocks” (英語). Organisms Diversity & Evolution 19 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1007/s13127-019-00390-7. ISSN 1618-1077.

- ^ Krämer, Jonas; Pohl, Hans; Predel, Reinhard (2019-04-15). “Venom collection and analysis in the pseudoscorpion Chelifer cancroides (Pseudoscorpiones: Cheliferidae)” (英語). Toxicon 162: 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.009. ISSN 0041-0101.

- ^ Cushing, Paula E.; Brookhart, Jack O.; Kleebe, Hans-Joachim; Zito, Gary; Payne, Peter (2005-10-01). “The suctorial organ of the Solifugae (Arachnida, Solifugae)” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 34 (4): 397–406. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2005.02.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b Wolff, Jonas O.; Schönhofer, Axel L.; Martens, Jochen; Wijnhoven, Hay; Taylor, Christopher K.; Gorb, Stanislav N. (2016-07-01). “The evolution of pedipalps and glandular hairs as predatory devices in harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones)”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 177 (3): 558–601. doi:10.1111/zoj.12375. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Wolff, Jonas O.; Schönhofer, Axel L.; Schaber, Clemens F.; Gorb, Stanislav N. (2014-10-01). “Gluing the ‘unwettable’: soil-dwelling harvestmen use viscoelastic fluids for capturing springtails” (英語). Journal of Experimental Biology 217 (19): 3535–3544. doi:10.1242/jeb.108852. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 25274325.

- ^ Dansk naturhistorisk forening (1907). Danmarks fauna; illustrerede haandbøger over den danske dyreverden... MBLWHOI Library. København, G.E.C. Gad

- ^ Talarico, G.; Palacios-Vargas, J.G.; Alberti, G. (2008-11). “The pedipalp of Pseudocellus pearsei (Ricinulei, Arachnida) – ultrastructure of a multifunctional organ” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 37 (6): 511–521. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2008.02.001.

- ^ Bolton, Samuel J. (2022-02-25). “Proteonematalycus wagneri Kethley reveals where the opisthosoma begins in acariform mites” (英語). PLOS ONE 17 (2): e0264358. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264358. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8880937. PMID 35213630.

- ^ Rowland, J. Mark; Sissom, W. David (1980). “Report on a Fossil Palpigrade from the Tertiary of Arizona, and a Review of the Morphology and Systematics of the Order (Arachnida: Palpigradida)”. The Journal of Arachnology 8 (1): 69–86. ISSN 0161-8202.

- ^ Cano-Sánchez, Esperanza; López-González, Pablo J. (2016-12-15). “Basal articulation of the palps and ovigers in Antarctic Colossendeis (Pycnogonida; Colossendeidae)” (英語). Helgoland Marine Research 70 (1). doi:10.1186/s10152-016-0474-7. ISSN 1438-387X.

- ^ a b Dietz, Lars; Dömel, Jana S.; Leese, Florian; Lehmann, Tobias; Melzer, Roland R. (2018-03-15). “Feeding ecology in sea spiders (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida): what do we know?” (英語). Frontiers in Zoology 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s12983-018-0250-4. ISSN 1742-9994. PMC 5856303. PMID 29568315.

- ^ a b Telford, Maximilian J.; Thomas, Richard H. (1998-09-01). “Expression of homeobox genes shows chelicerate arthropods retain their deutocerebral segment” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95 (18): 10671–10675. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 9724762.

- ^ Damen, Wim G. M. (2002-03-01). “Parasegmental organization of the spider embryo implies that the parasegment is an evolutionary conserved entity in arthropod embryogenesis” (英語). Development 129 (5): 1239–1250. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 11874919.

- ^ Jager, Muriel; Murienne, Jérôme; Clabaut, Céline; Deutsch, Jean; Guyader, Hervé Le; Manuel, Michaël (2006-05). “Homology of arthropod anterior appendages revealed by Hox gene expression in a sea spider” (英語). Nature 441 (7092): 506–508. doi:10.1038/nature04591. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Manuel, Michaël; Jager, Muriel; Murienne, Jérôme; Clabaut, Céline; Guyader, Hervé Le (2006-07-01). “Hox genes in sea spiders (Pycnogonida) and the homology of arthropod head segments” (英語). Development Genes and Evolution 216 (7): 481–491. doi:10.1007/s00427-006-0095-2. ISSN 1432-041X.

- ^ Brenneis, Georg; Ungerer, Petra; Scholtz, Gerhard (2008-11). “The chelifores of sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) are the appendages of the deutocerebral segment”. Evolution & Development 10 (6): 717–724. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00285.x. ISSN 1525-142X. PMID 19021742.

- ^ a b Mittmann, Beate; Scholtz, Gerhard (2003-02-01). “Development of the nervous system in the "head" of Limulus polyphemus (Chelicerata: Xiphosura): morphological evidence for a correspondence between the segments of the chelicerae and of the (first) antennae of Mandibulata” (英語). Development Genes and Evolution 213 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1007/s00427-002-0285-5. ISSN 1432-041X.

- ^ Harzsch, Steffen; Wildt, Miriam; Battelle, Barbara; Waloszek, Dieter (2005-07-01). “Immunohistochemical localization of neurotransmitters in the nervous system of larval Limulus polyphemus (Chelicerata, Xiphosura): evidence for a conserved protocerebral architecture in Euarthropoda” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 34 (3): 327–342. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2005.01.006. ISSN 1467-8039.