ヒトヘルペスウイルス6

| ヒトヘルペスウイルス6 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

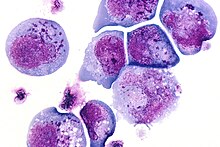

ヒトヘルペスウイルス6の電子顕微鏡写真

| |||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| 種 | |||||||||||||||

|

ヒトヘルペスウイルス6 (Human herpesvirus 6; HHV-6)は、ヒトを主要な宿主とするヘルペスウイルス9種のうち[1]、Human betaherpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A)およびHuman betaherpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B)の2種の総称である。ウイルス学上はともにベータヘルペスウイルス亜科ロゼオロウイルス属に所属させる。

歴史

[編集]

1986年、ロバート・ギャロの研究チームがエイズや白血病の患者の末梢血由来単核球を培養している過程で、細胞核や細胞内に封入体を生じる大きく屈折性の高い細胞を見出した。電子顕微鏡観察により新奇のウイルスが発見され、Human B-Lymphotrophic Virus (HBLV)と命名された[2][3]。一連の研究から、彼らはHBLVをヒトヘルペスウイルス6 (HHV-6)と改名した[4][5]。

まもなくHHV-6は、良く似ているものの区別可能な2つの亜型6Aと6Bに分けられた。HHV-6Aは成人由来であることが多くより神経向性が強いのに対し[6][7][8]、HHV-6Bは突発性発疹を呈する乳幼児から検出されることが多い。この2つのウイルスは塩基配列上95%一致している[9]。2012年に公式に2つの種であることが認められた[1]。

分類

[編集]HHV-6AとHHV-6Bはともにベータヘルペスウイルス亜科ロゼオロウイルス属に所属するが、ヒトを宿主とするロゼオロウイルスとしては他にHHV-7がある[1]。ウイルス学上の学名は長らくhuman herpesvirus 6であったが、2012年に6Aと6Bがそれぞれ独立した種と認められ、その後2015年にhuman betaherpesvirus 6と改名されている。もっとも臨床上human herpesvirus 6(あるいは6A/6B)と呼ぶことは差し支えない。

構造

[編集]HHV-6のウイルス粒子は直径およそ200 nmである[3]。外側からエンベロープ、テグメント、カプシドという構造をしている。最外層のエンベロープは、ウイルス由来の糖タンパク質を含む宿主由来の脂質二重膜である。カプシドは正二十面体をしており、その内部に直鎖状二本鎖DNAを含んでいる。

ゲノム

[編集]

HHV-6のゲノムは直鎖状二本鎖DNAから構成されている。両端に8-10 kbの直列反復配列があり、その内部に143-145 kbのユニークセグメントがある[11]。両端の直列反復配列はDRLとDRRと呼ばれており、ここにpac-1とpac-2という、ヘルペスウイルスに共通の分断・パッケージ化シグナルが含まれている。またここにはヒトのテロメアと同じTTAGGGのくり返しが15回から180回含まれている[12][13]。ユニークセグメントにはベータヘルペスウイルス科に共通する遺伝子ブロック(U2-U19)と、ヘルペスウイルス目に特徴的な7つのコア遺伝子ブロック(U27-U37, U38-U40, U41-U46, U48-U53, U56-U57, U66EX2-U77, U81-U82)があり、後者にはウイルスゲノムの複製、分断、パッケージ化に関わる保存的な遺伝子群がコードされている。複製起点(oriLyt)はDNA複製の開始する場所である[10]。

ウイルスの侵入

[編集]ウイルス受容体

[編集]HHV-6のウイルス粒子がヒトの細胞に侵入する際には、補体系の制御に関わるCD46を受容体として利用している。CD46分子にはオルタナティブスプライシングによって少なくとも14種のアイソフォームが生じるが、その全てがHHV-6Aに結合しうる[14]。CD46に結合するウイルス側のリガンドは、gH/gL/gQ1/gQ2から成る糖タンパク質複合体である[15][16][11]。

唾液腺

[編集]唾液腺が感染源になると考えられている[12]。

白血球

[編集]T細胞は特にHHV-6に感受性が高いと考えられている[17]。

神経系

[編集]150以上の検死例の分析から嗅覚組織においてHHV-6の存在量が多く、ここが中枢神経系への侵入点だと考えられている[9]。これは単純ヘルペスウイルスでの知見とも符合している[18]。とりわけ嗅神経鞘細胞がHHV-6の侵入に重要な役割を演じると考えられている[9]。

細胞内での活動

[編集]細胞へ侵入したウイルスは2通りの感染様式を示す。

活動性感染

[編集]活動性感染は、直鎖状のゲノムが環状化することで起きる。この過程は単純ヘルペスウイルスで最初に報告された[13]。環状化のあと"immediate early"遺伝子群が発現し、それが転写活性化因子として働くと推測されている[19]。続いて"early"遺伝子群が発現してウイルス由来DNAポリメラーゼを活性化し、ローリングサークル型複製を引き起こす[12]。その結果、ゲノムが直列に長く繰り返したコンカテマーが形成される[20]。コンカテマーはpac-1とpac-2領域の間で分断されて、個々のウイルス粒子へとパッケージ化される[13]。

非活動性感染

[編集]新たに感染を受けた細胞の全てでローリングサークル型複製が始まるわけではない。全てのベータヘルペスウイルスは潜伏感染を行うが[21]、HHV-6の場合は環状のエピソームとして潜伏するのではなく、ヒト染色体のサブテロメア領域に組み込まれることで潜伏すると考えられている[8]。これはHHV-6ゲノムの両端の反復配列にテロメア配列が含まれていることで可能になっている。

ヒトの染色体のうち、9、17、18、19、22番に組み込まれることが多く、その他10番や11番にも認められる[22][20]。おおよそ7000万人がこのように染色体に組み込まれたHHV-6を保持していると推定されている[8][20]。

この非活動性の潜伏期に特異的に発現する遺伝子がいくつか知られている。これらはゲノムを維持し宿主細胞が破壊されることを防ぐことに関わっている[22]。たとえばU94タンパク質はアポトーシス関連遺伝子を抑制し、テロメアへの組み込みを補助すると考えられている[12]。こうしてテロメアに格納されたウイルスは、断続的に再活性化を行う[22]。

再活性化

[編集]再活性化の特異的な引き金はわかっていない。傷害や物理的心理的ストレス、ホルモンバランスの不調などが関わると示唆する研究者もいる[23]。ヒストン脱アセチル化酵素の阻害剤で実験的に再活性化を引き起こせるという報告がある。再活性化が起きると、上述のようにローリングサークル型複製によってコンカテマーが形成される[12]。

相互作用

[編集]HHV-6は基本的にヒトを宿主とし、ウイルスの亜型によっては致死的な疾病を引き起こすこともあるが、片利的に共生しているといえる[24]。一方で、HHV-6はT細胞に共感染することでHIV-1の進展を助長することが示されている[25]。HHV-6はHIV受容体であるCD4の発現を亢進するため、HIVに感受性の細胞を増やすのである。またHHV-6感染によりHIV-1の発現を増強する、TNF-α、IL-1β、IL-8といった炎症性サイトカインの産生が増加することが示されている[26][27]。さらに、ブタオザルを用いた実験では、HHV-6Aの共感染によって、HIV感染からAIDS発症への進行が劇的に加速されることが示されている[28]。

HHV-6はEBウイルス(HHV-4)の活性化に関与することも示されている[18]。

疫学

[編集]年齢

[編集]ヒトは低年齢のうちに、早い場合には出生後1月以内にウイルスを獲得する。HHV-6の初感染はアメリカ合衆国において発熱による新生児救急外来受診の20%に関わるとされ[29][30]、より重篤な、脳炎、リンパ節腫脹、心筋炎、骨髄抑制といった症状にも関連している。ウイルス保有率は年齢ととも増加し、これは乳児を感染から守っている母体由来の抗体が失われることによると考える者もある[24]。

年齢と血清陽性率の関係には不一致がある。年齢の増加にともない、血清陽性率が減少するという報告、有意な減少はないとする報告、増加するという報告がある。初感染の後、唾液腺や造血幹細胞などで終生潜伏し続ける。

地理的分布

[編集]HHV-6は世界中に広く分布している。生後13ヶ月における感染率は、アメリカ合衆国、イギリス、日本、台湾で64-83%と高率である[24][31]。また成人における血清陽性率は、タンザニア、マレーシア、タイ、ブラジルの多様な集団で39%から80%である[24]。同じ場所に住む人々の間では、民族や性による有意な差はない。HHV-6Bは世界中のほとんど全ての集団に存在するのに対し、HHV-6Aは日本、北アメリカ、ヨーロッパではやや少ない[24]。

感染経路

[編集]ウイルス粒子が唾液中に排出されることが最も多い感染経路だと考えられている。HHV-6BとHHV-7はともに唾液中に見付かるが、前者の方が頻度が低い。HHV-6の唾液中の存在率は3-90%と研究によってばらつきが大きい[24]。ウイルスは唾液腺に感染、潜伏し、時々再活性化して他の宿主へと感染を拡げる[12]。

垂直感染もあり、アメリカ合衆国では出生の1%で起きている[19][32]。これはウイルスゲノムが個体の全ての細胞に見出されることで簡単に検出できる。

臨床的意義

[編集]古典的にはHHV-6Bの初感染は高熱の後に発疹を呈する突発性発疹を引き起こすとされる。しかし発疹は必ずしもHHV-6感染の特徴ではなく、HHV-6以外の感染と同程度(10-20%)の患児にしか起こらない。一方で40°Cを越す高熱はHHV-6感染に特徴的で、ほかに倦怠感、過敏、鼓膜の炎症などが挙げられる[24]。

ウイルスの鑑別は、特にHHV-6Bの場合、感染の副作用のために重要になる。この感染を示す発疹のような徴候は、抗生物質を処方された患者では気付かれにくい、なぜなら抗生物質の副作用だと誤解しがちだから[24]。HHV-6Bは突発性発疹だけでなく他の疾患とも関係している。肝炎、熱性けいれん、脳炎など。HHV-6B感染により突発性発疹を呈する患児は3から5日間の発熱、胴体、首、顔の発疹、そして時折熱性けいれんを示すが、これらは常に一緒に出るわけではない。ほとんどの場合子供のうちに感染するため、成人が初感染を受ける事は稀である。しかし成人における初感染ではより重篤な症状を示す傾向がある[24]。

潜伏状態のウイルスは時折再活性化し、アメリカ合衆国の健康な成人からでも20-25%の割合でDNAを検出できる。免疫反応が正常な状態では再活性化しても無徴候に終わるが、免疫抑制状態では深刻な併発症となり得る。HHV-6の再活性化は臓器移植患者では深刻な疾患を引き起こし、移植片拒絶に繋がることもある。またHIV/AIDSのように、HHV-6の再活性化により全身性感染を引き起こし末端臓器障害から死亡に至ることもある。人口のほぼ100%が保有しているとはいえ、たいてい3歳までに感染しており、成人の初感染は稀である。アメリカ合衆国では、HHV-6Aが多く、それはより病原性が高くより神経向性があり、中枢神経系疾患につながるから。

HHV-6は多発性硬化症の患者で報告されているほか[33]、慢性疲労症候群[34]、線維筋痛症、AIDS[35]、視神経炎、がん、側頭葉てんかん[36]、うつ病[37]などの疾患の共役因子としても報告されている。

治療

[編集]HHV-6感染の治療に対して承認された薬剤はないが、サイトメガロウイルス感染症への治療薬(バルガンシクロビル、ガンシクロビル[38]、シドフォビル、ホスカルネット)は奏効している[19]。これらの薬剤はデオキシヌクレオシド三リン酸と競合してDNA重合を阻害するか[38]、ウイルスのDNAポリメラーゼを特異的に不活化する[39]ことを狙って投与されている。

HHV-6再活性化が移植手術後に起きた場合の治療法を見つけるのは、移植医療が免疫抑制剤を前提としているが故に困難かもしれない[40]。

出典・脚注

[編集]- ^ a b c Adams, M. J.; Carstens, E. B. (2012). “Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2012)”. Archives of Virology 157 (7): 1411–1422. doi:10.1007/s00705-012-1299-6. PMID 22481600.

- ^ Anderson, L. (1988). “Human Retrovirus Family: Cancer, Central Nervous System Disease, and AIDS”. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute 80 (13): 987–9. doi:10.1093/jnci/80.13.987. PMID 2842514.

- ^ a b Salahuddin, S.; Ablashi, D.; Markham, P.; Josephs, S.; Sturzenegger, S; Kaplan, M; Halligan, G; Biberfeld, P et al. (1986). “Isolation of a new virus, HBLV, in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders”. Science 234 (4776): 596–601. Bibcode: 1986Sci...234..596Z. doi:10.1126/science.2876520. PMID 2876520.

- ^ Ablashi, DV; Salahuddin, SZ; Josephs, SF; Imam, F; Lusso, P; Gallo, RC; Hung, C; Lemp, J et al. (1987). “HBLV (or HHV-6) in human cell lines”. Nature 329 (6136): 207. Bibcode: 1987Natur.329..207A. doi:10.1038/329207a0. PMID 3627265.

- ^ Ablashi, Dharam; Krueger, Gerhard (2006). Human Herpesvirus-6 General Virology, Epidemiology and Clinical Pathology. (2nd ed.). Burlington: Elsevier. p. 7. ISBN 9780080461281

- ^ De Bolle, L.; Van Loon, J.; De Clercq, E.; Naesens, L. (2005). “Quantitative analysis of human herpesvirus 6 cell tropism”. Journal of Medical Virology 75 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1002/jmv.20240. PMID 15543581.

- ^ Kofman, Alexander; Marcinkiewicz, Lucasz; Dupart, Evan; Lyshchev, Anton; Martynov, Boris; Ryndin, Anatolii; Kotelevskaya, Elena; Brown, Jay et al. (2011). “The roles of viruses in brain tumor initiation and oncomodulation”. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 105 (3): 451–66. doi:10.1007/s11060-011-0658-6. PMC 3278219. PMID 21720806.

- ^ a b c Arbuckle, J. H.; Medveczky, M. M.; Luka, J.; Hadley, S. H.; Luegmayr, A.; Ablashi, D.; Lund, T. C.; Tolar, J. et al. (2010). “The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (12): 5563–5568. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.5563A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913586107. PMC 2851814. PMID 20212114.

- ^ a b c Harberts, E.; Yao, K.; Wohler, J. E.; Maric, D.; Ohayon, J.; Henkin, R.; Jacobson, S. (2011). “Human herpesvirus-6 entry into the central nervous system through the olfactory pathway”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (33): 13734–9. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10813734H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1105143108. PMC 3158203. PMID 21825120.

- ^ a b Dominguez, G.; Dambaugh, T. R.; Stamey, F. R.; Dewhurst, S.; Inoue, N.; Pellett, P. E. (1999). “Human herpesvirus 6B genome sequence: Coding content and comparison with human herpesvirus 6A”. Journal of Virology 73 (10): 8040–8052. PMC 112820. PMID 10482553.

- ^ a b Tang, Huamin; Kawabata, Akiko; Yoshida, Mayumi; Oyaizu, Hiroko; Maeki, Takahiro; Yamanishi, Koichi; Mori, Yasuko (2010). “Human herpesvirus 6 encoded glycoprotein Q1 gene is essential for virus growth”. Virology 407 (2): 360–7. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.018. PMID 20863544.

- ^ a b c d e f Arbuckle, Jesse H.; Medveczky, Peter G. (2011). “The molecular biology of human herpesvirus-6 latency and telomere integration”. Microbes and Infection 13 (8–9): 731–41. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2011.03.006. PMC 3130849. PMID 21458587.

- ^ a b c Borenstein, R.; Frenkel, N. (2009). “Cloning human herpes virus 6A genome into bacterial artificial chromosomes and study of DNA replication intermediates”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (45): 19138–19143. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10619138B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908504106. PMC 2767366. PMID 19858479.

- ^ Greenstone, H. L.; Santoro, F; Lusso, P; Berger, EA (2002). “Human Herpesvirus 6 and Measles Virus Employ Distinct CD46 Domains for Receptor Function”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (42): 39112–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206488200. PMID 12171934.

- ^ Kawabata, A.; Oyaizu, H.; Maeki, T.; Tang, H.; Yamanishi, K.; Mori, Y. (2011). “Analysis of a Neutralizing Antibody for Human Herpesvirus 6B Reveals a Role for Glycoprotein Q1 in Viral Entry”. Journal of Virology 85 (24): 12962–71. doi:10.1128/JVI.05622-11. PMC 3233151. PMID 21957287.

- ^ Mori, Yasuko (2009). “Recent topics related to human herpesvirus 6 cell tropism”. Cellular Microbiology 11 (7): 1001–6. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01312.x. PMID 19290911.

- ^ J Exp Med. 1995 Apr 1;181(4):1303–10. Infection of gamma/delta T lymphocytes by human herpesvirus 6: transcriptional induction of CD4 and susceptibility to HIV infection. Lusso P, Garzino-Demo A, Crowley RW, Malnati MS.

- ^ a b Liedtke, W.; Opalka, B.; Zimmermann, C.W.; Lignitz, E. (1993). “Age distribution of latent herpes simplex virus 1 and varicella-zoster virus genome in human nervous tissue”. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 116 (1): 6–11. doi:10.1016/0022-510X(93)90082-A. PMID 8389816.

- ^ a b c Flamand, Louis; Komaroff, Anthony L.; Arbuckle, Jesse H.; Medveczky, Peter G.; Ablashi, Dharam V. (2010). “Review, part 1: Human herpesvirus-6-basic biology, diagnostic testing, and antiviral efficacy”. Journal of Medical Virology 82 (9): 1560–8. doi:10.1002/jmv.21839. PMID 20648610.

- ^ a b c Morissette, G.; Flamand, L. (2010). “Herpesviruses and Chromosomal Integration”. Journal of Virology 84 (23): 12100–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.01169-10. PMC 2976420. PMID 20844040.

- ^ Potenza, Leonardo; Barozzi, Patrizia; Torelli, Giuseppe; Luppi, Mario (2010). “Translational challenges of human herpesvirus 6 chromosomal integration”. Future Microbiology 5 (7): 993–5. doi:10.2217/fmb.10.74. PMID 20632798.

- ^ a b c Kaufer, B. B.; Jarosinski, K. W.; Osterrieder, N. (2011). “Herpesvirus telomeric repeats facilitate genomic integration into host telomeres and mobilization of viral DNA during reactivation”. Journal of Experimental Medicine 208 (3): 605–15. doi:10.1084/jem.20101402. PMC 3058580. PMID 21383055.

- ^ Isegawa, Yuji; Matsumoto, Chisa; Nishinaka, Kazuko; Nakano, Kazushi; Tanaka, Tatsuya; Sugimoto, Nakaba; Ohshima, Atsushi (2010). “PCR with quenching probes enables the rapid detection and identification of ganciclovir-resistance-causing U69 gene mutations in human herpesvirus 6”. Molecular and Cellular Probes 24 (4): 167–77. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2010.01.002. PMID 20083192.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Braun, DK; Dominguez, G; Pellett, PE (1997). “Human herpesvirus 6”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 10 (3): 521–67. doi:10.1128/CMR.10.3.521. PMC 172933. PMID 9227865.

- ^ Lusso, Paolo; De Maria, Andrea; Malnati, Mauro; Lori, Franco; Derocco, Susan E.; Baseler, Michael; Gallo, Robert C. (1991). “Induction of CD4 and susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in human CD8+ T lymphocytes by human herpesvirus 6”. Nature 349 (6309): 533–5. Bibcode: 1991Natur.349..533L. doi:10.1038/349533a0. PMID 1846951.

- ^ Arena, A; Liberto, MC; Capozza, AB; Focà, A (1997). “Productive HHV-6 infection in differentiated U937 cells: Role of TNF alpha in regulation of HHV-6”. The New Microbiologica 20 (1): 13–20. PMID 9037664.

- ^ Inagi, Reiko; Guntapong, Ratigorn; Nakao, Masayuki; Ishino, Yoshizumi; Kawanishi, Kazunobu; Isegawa, Yuji; Yamanishi, Koichi (1996). “Human herpesvirus 6 induces IL-8 gene expression in human hepatoma cell line, Hep G2”. Journal of Medical Virology 49 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199605)49:1<34::AID-JMV6>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 8732869.

- ^ Lusso, P.; Crowley, R. W.; Malnati, M. S.; Di Serio, C.; Ponzoni, M.; Biancotto, A.; Markham, P. D.; Gallo, R. C. (2007). “Human herpesvirus 6A accelerates AIDS progression in macaques”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (12): 5067–72. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..104.5067L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700929104. JSTOR 25427145. PMC 1829265. PMID 17360322.

- ^ Hall, Caroline Breese; Long, Christine E.; Schnabel, Kenneth C.; Caserta, Mary T.; McIntyre, Kim M.; Costanzo, Maria A.; Knott, Anne; Dewhurst, Stephen et al. (1994). “Human Herpesvirus-6 Infection in Children -- A Prospective Study of Complications and Reactivation”. New England Journal of Medicine 331 (7): 432–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199408183310703. PMID 8035839.

- ^ Newly Found Herpes Virus Is Called Major Cause of Illness in Young, New York Times

- ^ Okuno, T; Takahashi, K; Balachandra, K; Shiraki, K; Yamanishi, K; Takahashi, M; Baba, K (1989). “Seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 6 infection in normal children and adults”. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 27 (4): 651–3. PMC 267390. PMID 2542358.

- ^ Araujo, A.; Pagnier, A.; Frange, P.; Wroblewski, I.; Stasia, M.-J.; Morand, P.; Plantaz, D. (2011). “Syndrome d'activation lymphohistiocytaire associé à une infection à Burkholderia cepacia complex chez un nourrisson révélant une granulomatose septique et une intégration génomique du virus HHV-6 [Lymphohistiocytic activation syndrome and Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in a child revealing chronic granulomatous disease and chromosomal integration of the HHV-6 genome]” (French). Archives de Pédiatrie 18 (4): 416–9. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2011.01.006. PMID 21397473.

- ^ Alvarez-Lafuente, R.; Martin-Estefania, C.; De Las Heras, V.; Castrillo, C.; Cour, I.; Picazo, J.J.; Varela De Seijas, E.; Arroyo, R. (2002). “Prevalence of herpesvirus DNA in MS patients and healthy blood donors”. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 105 (2): 95–9. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.1o050.x. PMID 11903118.

- ^ Komaroff, Anthony L. (2006). “Is human herpesvirus-6 a trigger for chronic fatigue syndrome?”. Journal of Clinical Virology 37: S39–46. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(06)70010-5. PMID 17276367.

- ^ HHV-6 and AIDS Archived 8 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Wisconsin Viral Research Group

- ^ Fotheringham, Julie; Donati, Donatella; Akhyani, Nahid; Fogdell-Hahn, Anna; Vortmeyer, Alexander; Heiss, John D.; Williams, Elizabeth; Weinstein, Steven et al. (2007). “Association of Human Herpesvirus-6B with Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy”. PLoS Medicine 4 (5): e180. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040180. PMC 1880851. PMID 17535102.[信頼性の低い医学の情報源?]

- ^ Kobayashi, Nobuyuki; Oka, Naomi; Takahashi, Mayumi; Shimada, Kazuya; Ishii, Azusa; Tatebayashi, Yoshitaka; Shigeta, Masahiro; Yanagisawa, Hiroyuki et al. (2020). “Human Herpesvirus 6B Greatly Increases Risk of Depression by Activating Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis during Latent Phase of Infection”. ScienceDirect 23 (6). doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101187. PMC 7298549. PMID 32534440.

- ^ a b Nakano, Kazushi; Nishinaka, Kazuko; Tanaka, Tatsuya; Ohshima, Atsushi; Sugimoto, Nakaba; Isegawa, Yuji (2009). “Detection and identification of U69 gene mutations encoded by ganciclovir-resistant human herpesvirus 6 using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography”. Journal of Virological Methods 161 (2): 223–30. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.06.016. PMID 19559728.

- ^ Jaworska, J.; Gravel, A.; Flamand, L. (2010). “Divergent susceptibilities of human herpesvirus 6 variants to type I interferons”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (18): 8369–74. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.8369J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909951107. PMC 2889514. PMID 20404187.

- ^ Shiley, Kevin; Blumberg, Emily (2010). “Herpes Viruses in Transplant Recipients: HSV, VZV, Human Herpes Viruses, and EBV”. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 24 (2): 373–93. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2010.01.003. PMID 20466275.

外部リンク

[編集]- 奥野寿臣, 邵輝, 山西弘一、「ヒトヘルペスウイルス6」 『ウイルス』 1991年 41巻 2号 p.65-76, doi:10.2222/jsv.41.65